My THINK LIGHT series is my outlet for being a lighting geek. Perhaps I should rephrase that – this is my outlet for being a lighting pseudo-geek. I do love the science, geometry, biology, psychology, and technology of light, but I am no scientist, biologist, psychologist, or technologist. There is a limit to how geeky I can get because there are very real limits on my knowledge and understanding. I’m not that smart, so I learn enough to inform my work and then spend the rest of my time trying to make it happen.

I am no great researcher, but I do enjoy taking a look at light and boiling down the information into actionable knowledge. THINK LIGHT is a hybrid series that straddles the line of scientific understanding and action steps. That’s a rather long-winded disclaimer that if you came here looking for annotated bibliographies and charts comparing test group one to the control group…you’re in the wrong place.

Today I looked at my writing plan for the year and found only the phrase “near field of vision.” Apparently sometime in the last few months I thought it would be a good topic to explore. Nothing of particular use sprang to mind immediately, so I pulled out my tablet and started to research and sketch. What slowly took shape on the digital page was a very simple question: where does lighting go? And I found some answers you may find useful. But first, some pseudo-geeky stuff.

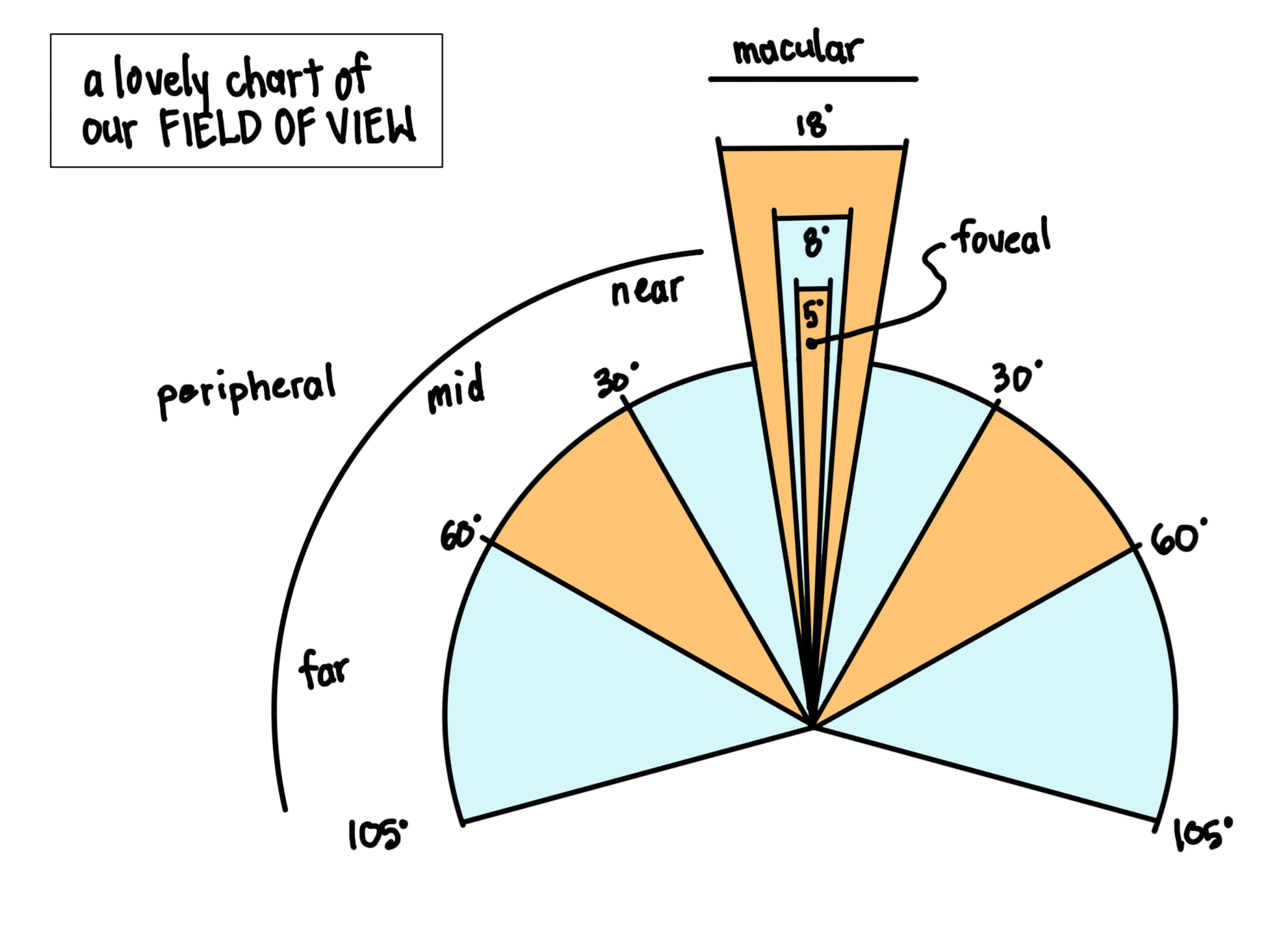

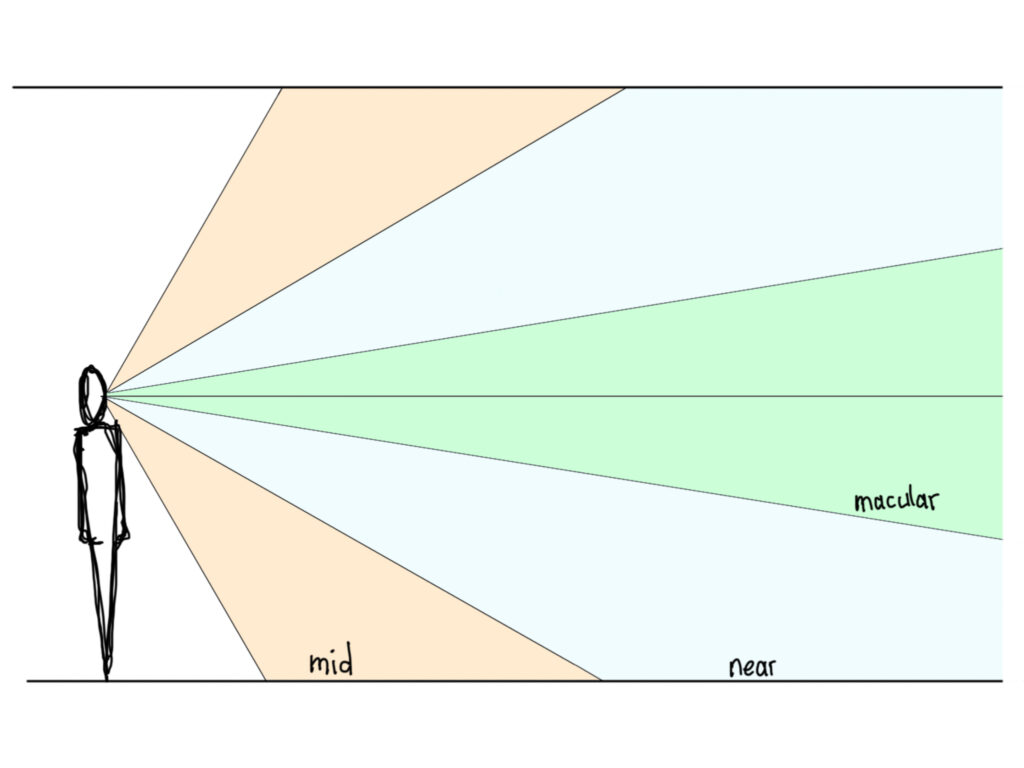

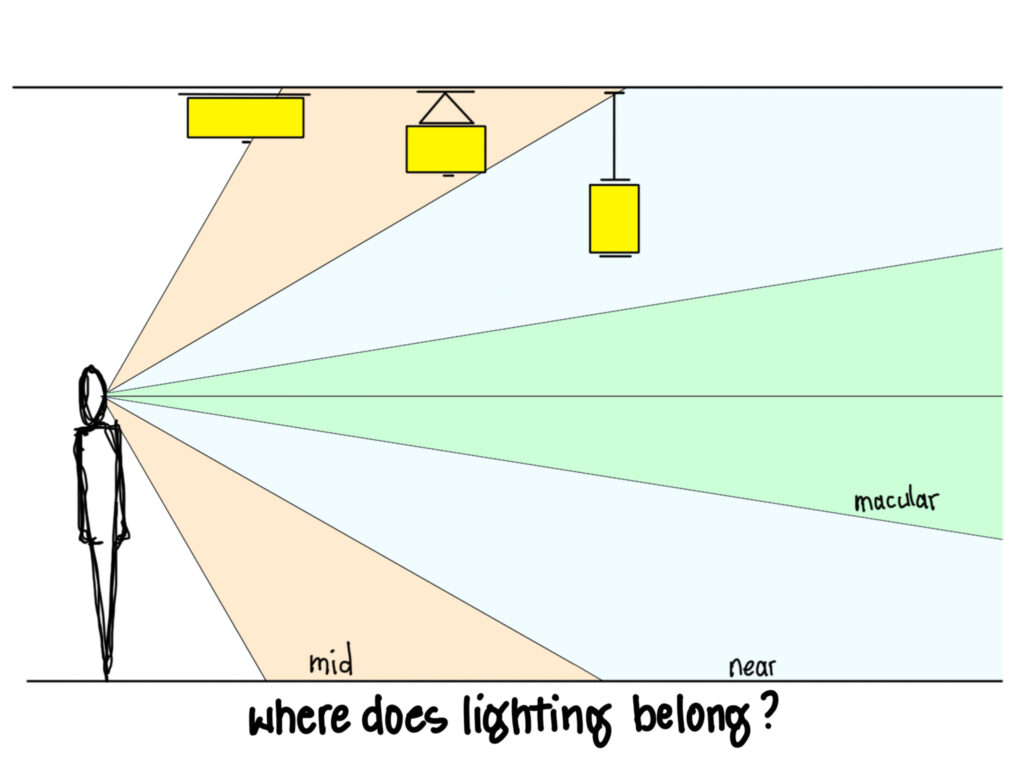

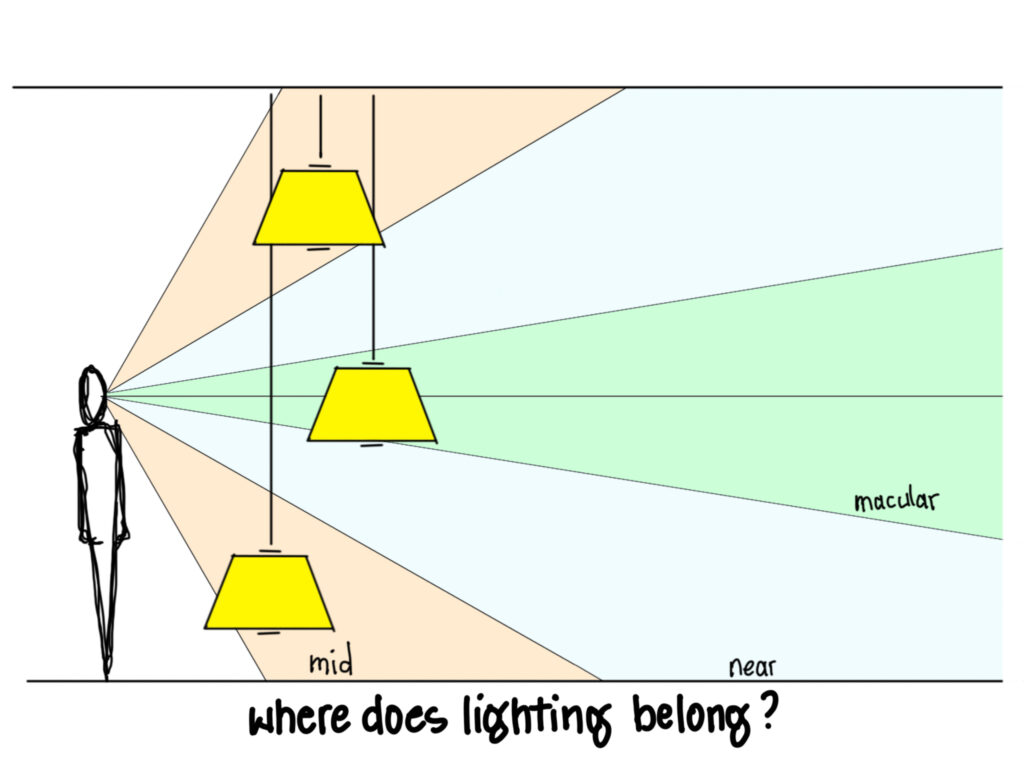

The near field of vision, or field of view, is narrow band of our eyesight in which we see shape and color, what our brain registers as walls and trees and chairs and an endlessly changing array of people, places, and things. At the very center of our field of view is our foveal or macular vision, a very narrow cone of sight that sees in focus. The foveal vision is what you are using to read these words. Look off to the right and you will still know there is a computer in front of you, but you will no longer be able to read the words.

Outside of that near field of view is the remainder of our peripheral vision, which mostly sees changes in light and dark (motion). All told, we see up to 110° in each direction, a pretty astounding feat that allows us to perceive motion even slightly behind us. Eyes are pretty cool. All these components of vision are important in lighting design, as light is the only thing that our eyes truly see. But the near field is perhaps the most important for us.

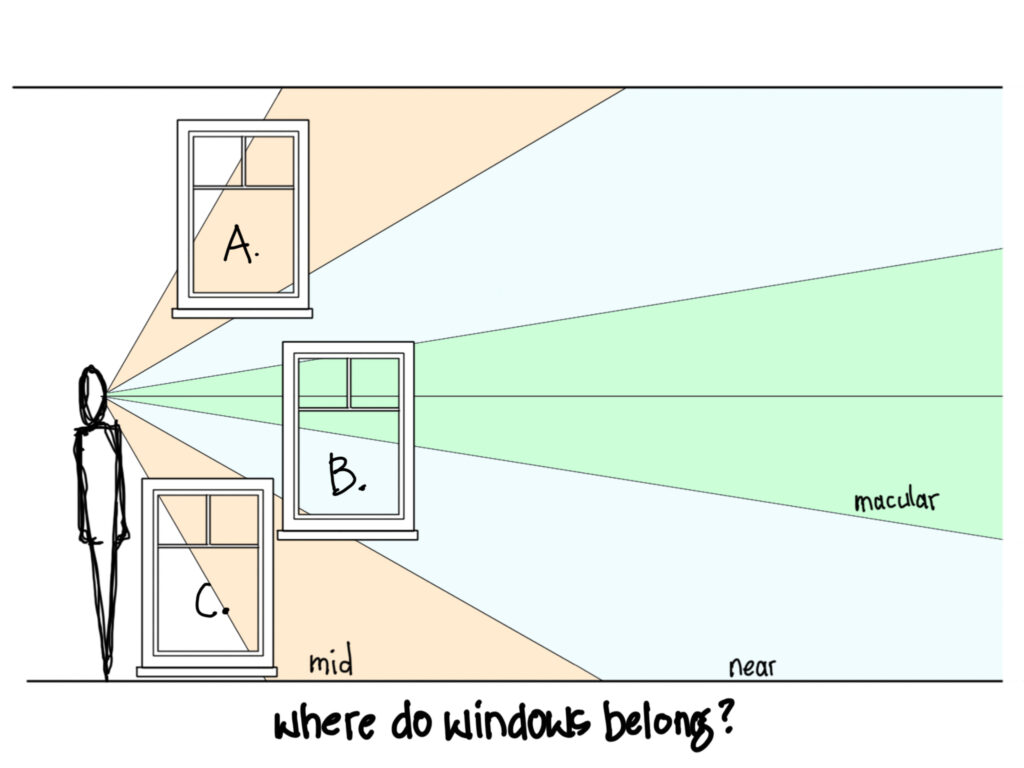

Intrinsically, most of us know where in our field of vision windows belong. Window A is too high, so we have a different name for them (clerestory windows or skylights) and a different use for them (not to see out but only to let light in). Window C is too low and so infrequently used that no common term comes to mind. They usually only show up in architectural mistakes or avant-garde design.

Window B is just right, and Goldilocks would be satisfied. Neither too high nor too low, most of our windows fall squarely within our near field of vision and allow us to see trees and buildings outside. This isn’t rocket science, right?

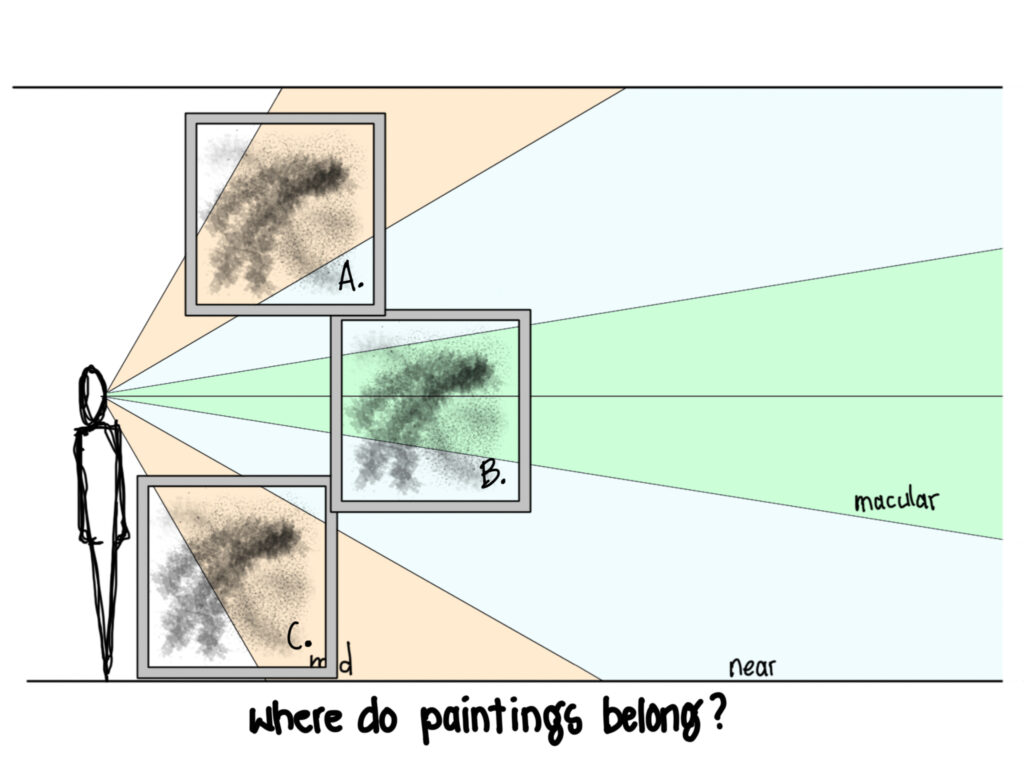

We also know where to hang paintings (though most of us hang them a bit too high). Painting A would be ridiculous, perhaps best used for a painting of great-great-great-grandfather looking down on us with historic disapproval. Painting C would be, well, dumb. And it would probably get dirty and kicked, too.

Painting B is in the sweet spot. We can see it in our near field of view and focus in on the detail with our macular/foveal/focused vision. This isn’t brain surgery, right?

Okay, now let’s talk lighting. We know where that goes, right? On the ceiling, of course! But wait…what am I trying to say here?

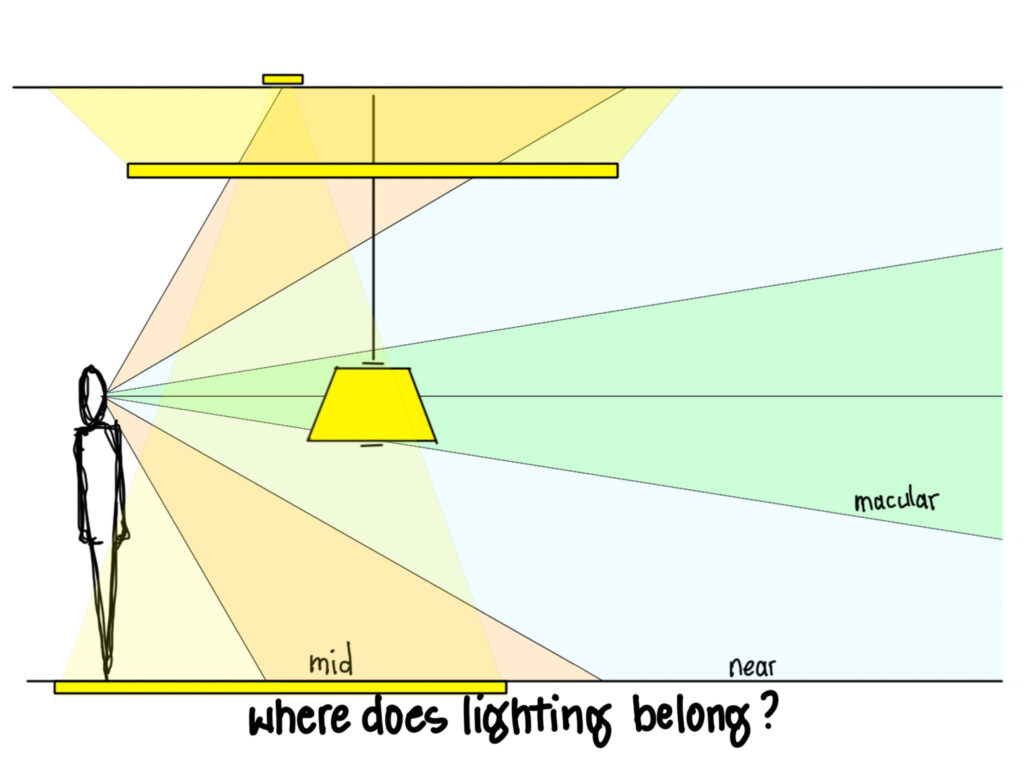

Lighting goes on the ceiling because that is the cheapest, easiest place to put it. Light on the ceiling doesn’t get blocked by chairs, kicked by children, or chewed on by dogs. Light on the ceiling is easy to wire, easy to install, and can look very tidy on an electrical plan.

There’s just one problem with light only from the ceiling. We have eyes, and our eyes have a near field of vision that is responsible for most of our comfort and conscious sight.

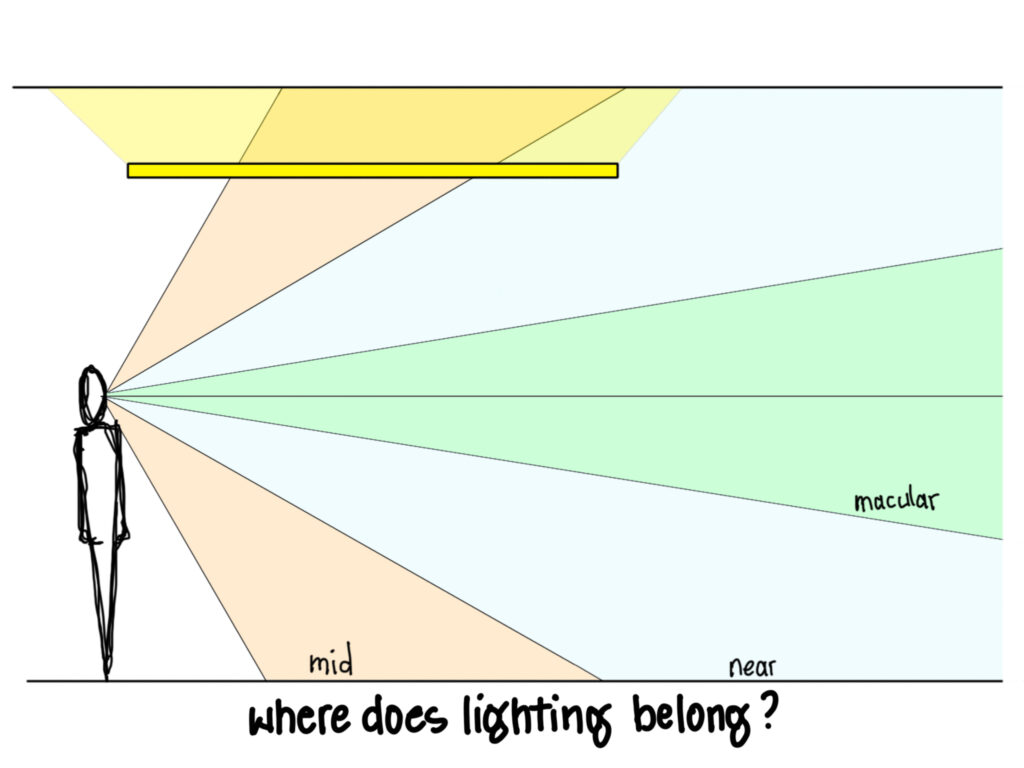

It’s not just residential lighting that falls prey to the “lighting belongs only on the ceiling” mistake. Commercial and institutional lighting can be even worse, relying entirely on light from outside our near field of vision. Cove lighting in homes and indirect light in offices and schools puts the most light on the ceiling. This can be an important part of good lighting, but it cannot be the only solution if we truly want to feel comfortable.

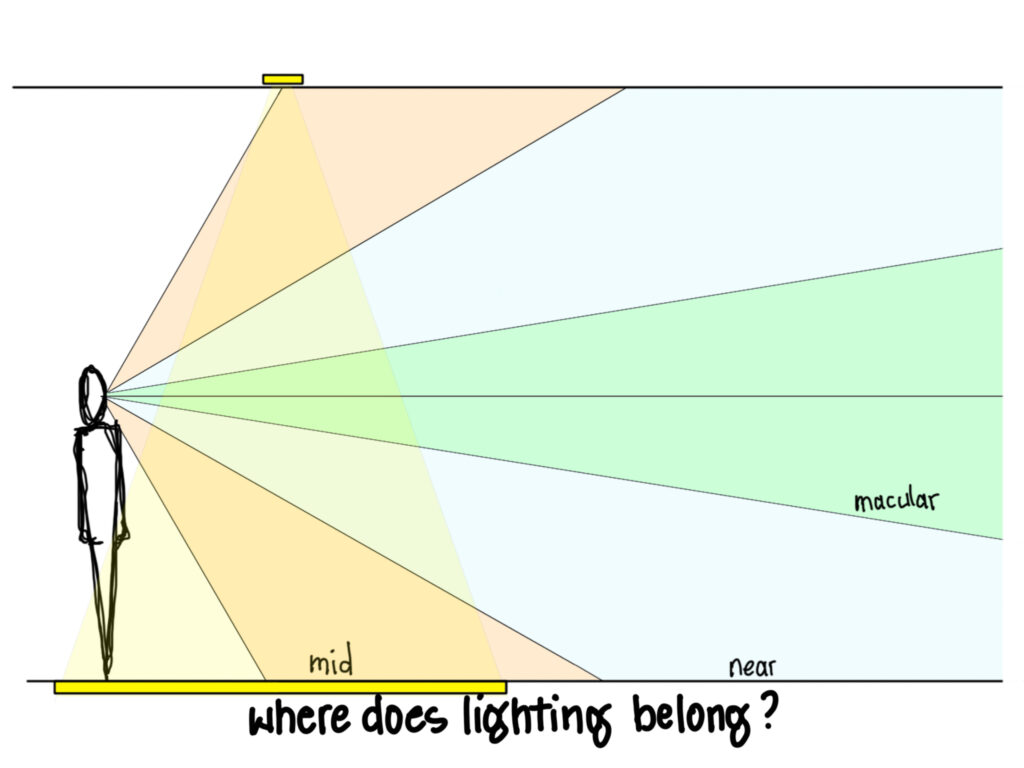

Perhaps the worst light-from-the-ceiling is a recessed downlight aimed at the floor. Glare above and too much light below, this approach leaves our near field of vision devoid of comfortable light. If I could wave a magic wand and change one thing about residential lighting, it would be to stop spilling light on the carpet when there are perfectly lovely things on our walls to illuminate. It looks better to light what we see in our near field of vision. And it feels better, too.

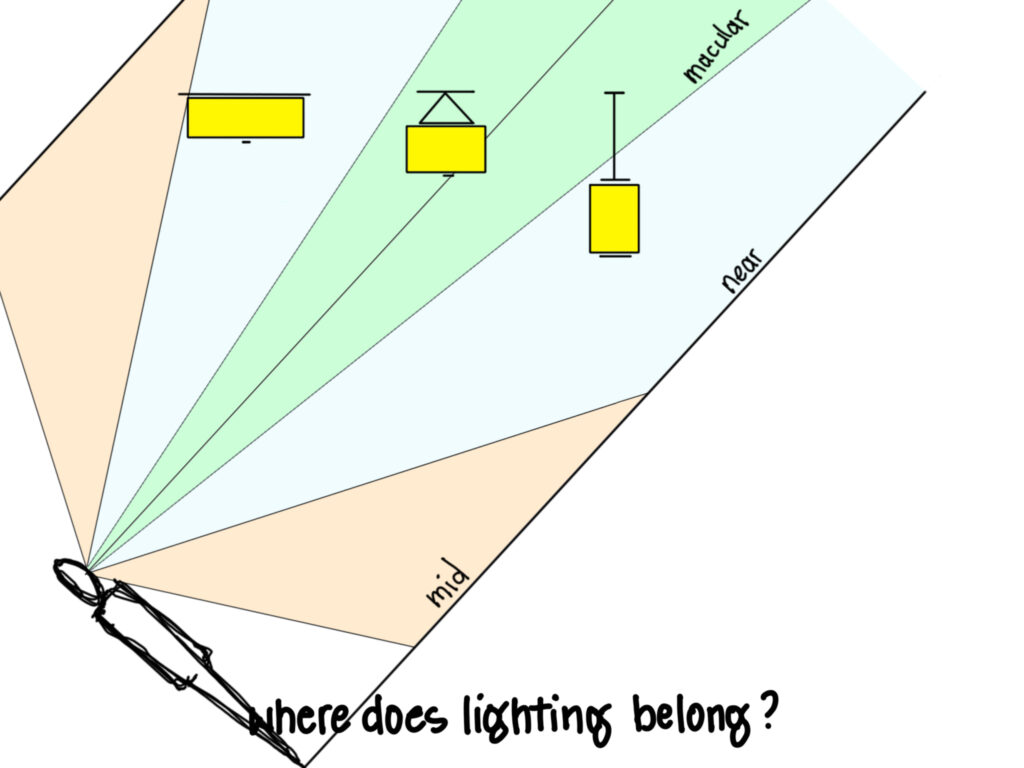

We have two choices to get lighting where it belongs. We can tilt ourselves into a reclining position and walk through life at a 60° slant, always about to fall over and never seeing what is in front of us. Not a particular good solution, as the image above reveals. But maybe we don’t need to bend our necks into uncomfortable positions, maybe we just need to reTHINK LIGHT. See what I did there?

Light can be introduced into our near field of view in a multitude of ways and putting them all here would end up a book instead of a blog post. One method of getting lighting where it belongs is to let go of the “lighting goes only on the ceiling” rule. Lamps, pendants, and wall sconces give us the option of putting soft glowing light sources in our near field of vision, making every waking moment more comfortable and pleasant. Pendants can be hung too high or too low; just right is found by understanding how our eyes are made.

Lighting design is not rocket science, but it is based in the science and biology of our eyes. It doesn’t matter how cheap and easy it is to install a wafer/disc light, it will never satisfy our eyes and, as a result, never serve our bodies best. A balanced approach, a comfortable home, an invigorating workplace will always take the near field of vision into account.

If we are not lighting for the ways our eyes are made, we are lighting for the wrong reasons. And we’re probably putting light in the wrong place.