Light plays a central role in many of the foundational stories of humanity. I am most familiar with the narrative in the Judeo-Christian stories of creation in which the first recorded words of Yahweh are “let there be light.” But light as an element of the divine is not restricted to modern Christianity and metaphors and gods can be found throughout history and across the globe.

Helios, the ancient Greek Titan, rode a chariot of fire into the sky each morning, a mythical sunrise to start the day. Zeus had his lightning bolts; Prometheus was both revered and punished for giving fire to humans.

Nearby, in ancient Egypt, Ra was a key deity and god of the sun. Just a little to the east, “God is light” was recorded in Islam’s Quran. God is described as a pillar of light in Hinduism; Diwali is a celebration of light’s triumph over darkness. Buddhism discusses inner light and points us towards enlightenment. Some light references we do not fully understand: England’s Stonehenge is precisely aligned with the sun at solstice, as are temples in Incan and Mayan civilizations and the stone circles in Senegal.

Our ancestors did not simply think light was important; light was divine to them. They recognized something we may have collectively forgotten: light is, regardless of religion or narrative, one of the first and most important gifts of the universe.

My view of human history is insignificant and not worth exploring in depth. Let’s just say that I like to think God spoke and there was a very, very big bang, a resulting universe of light that continues to expand and evolve millions of years later.

Beyond worship, light for human use has long impacted our development as a species. For thousands of years, we went inside our shelters and slept when the sun was not out to help us. We burned wood for light, heat, and food, and made smaller fires with tallow and wax. Whales were nearly hunted to extinction after we discovered their oil made for a brighter, cleaner source of light.

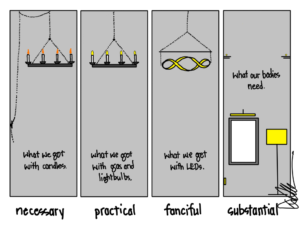

Modern lighting seems to draw heavily on candlelight, at least in its basic form and function. For centuries, candles were the luxury lighting of the wealthy. They could be grouped together in chandeliers hoisted above a room, an effect many of us replicate in our dining rooms today. When natural gas became a viable source of light, we simply piped it to the chandeliers and replaced candles with wicks that could burn cleaner and longer.

When gas was outdone by electric light, we pulled electric wires through the existing gas piping, replaced the wicks with bulbs, and electrified our chandeliers. Now, with LEDs, we are getting a little more creative with the shapes of our chandeliers, but still hanging them up in the center of our room, almost as if anywhere else would start a fire as candles might.

While we continue to use light as a metaphor in our religions and beliefs, practical light in our lives is no longer perceived as a gift of the divine. Somehow, light has become a commodity, a utility, as important and exciting as natural gas for heating or sewer pipes for carrying away waste. In residential construction, we know we must provide light in the home but see little value in delivering anything beyond the basics. Perhaps a few dollars are spent on a trendy chandelier, but we scrimp and save with the cheapest and fewest of lights elsewhere. Many of our homes are now lit by wafer-thin LED disk lights, easy to install but not good for us.

Yet some innate recognition of the divine, mystical, and magical power of light persists. Though we can have light wherever and whenever we want, our most memorable moments include sunrises, sunsets, and rainbows. We vacation under the sun, revel in blue skies, and relax under the stars. Indoors, we light candles for romance, burn fires for relaxation, and hang twinkle lights for celebrations. We may have commodified light in our homes, but our spirits still make light a central part of our lives.

Our modern approach to light and lighting must change, not because lighting designers need work or because our homes can look more beautiful, but because our bodies, minds, and planet need us to rethink light.

In my next Light Can Help Us post, I will return to the Red Velvet Cake theory and the five promises of light for another look. If we are to rethink light, it will begin with the very words we use to describe it.

Read more Light Can Help Us posts HERE.