Of all the moments of discovery, connection, and understanding provided at LightFair this year, none stirred my emotions or challenged my thinking as deeply as the fifty minutes allotted to the Light + Justice conference session. Led by Edward Bartholomew, Mark Loeffler, and Lya S. Osborn, the presentation shook up my thinking and clarified my focus. We do not need to change the way we light at home because it would be better. We need to change what we are doing because it could be just and fair and right.

A few years ago my wife and I streamed our way through the entire Downton Abbey series, finally taking in what millions had already enjoyed. The series focuses on a wealthy noble family in the early 1900’s in England, and the many servants that make the estate function. It falls into the category sometimes described as Upstairs/Downstairs stories, a dual focus on the wealthy living upstairs and the working-class toiling in the basement. When we watched the show, I had the requisite pity for the working class and the dual awe and disgust of the wealthy. Ah, how fortunate we are to live in an era beyond such dichotomy, I thought.

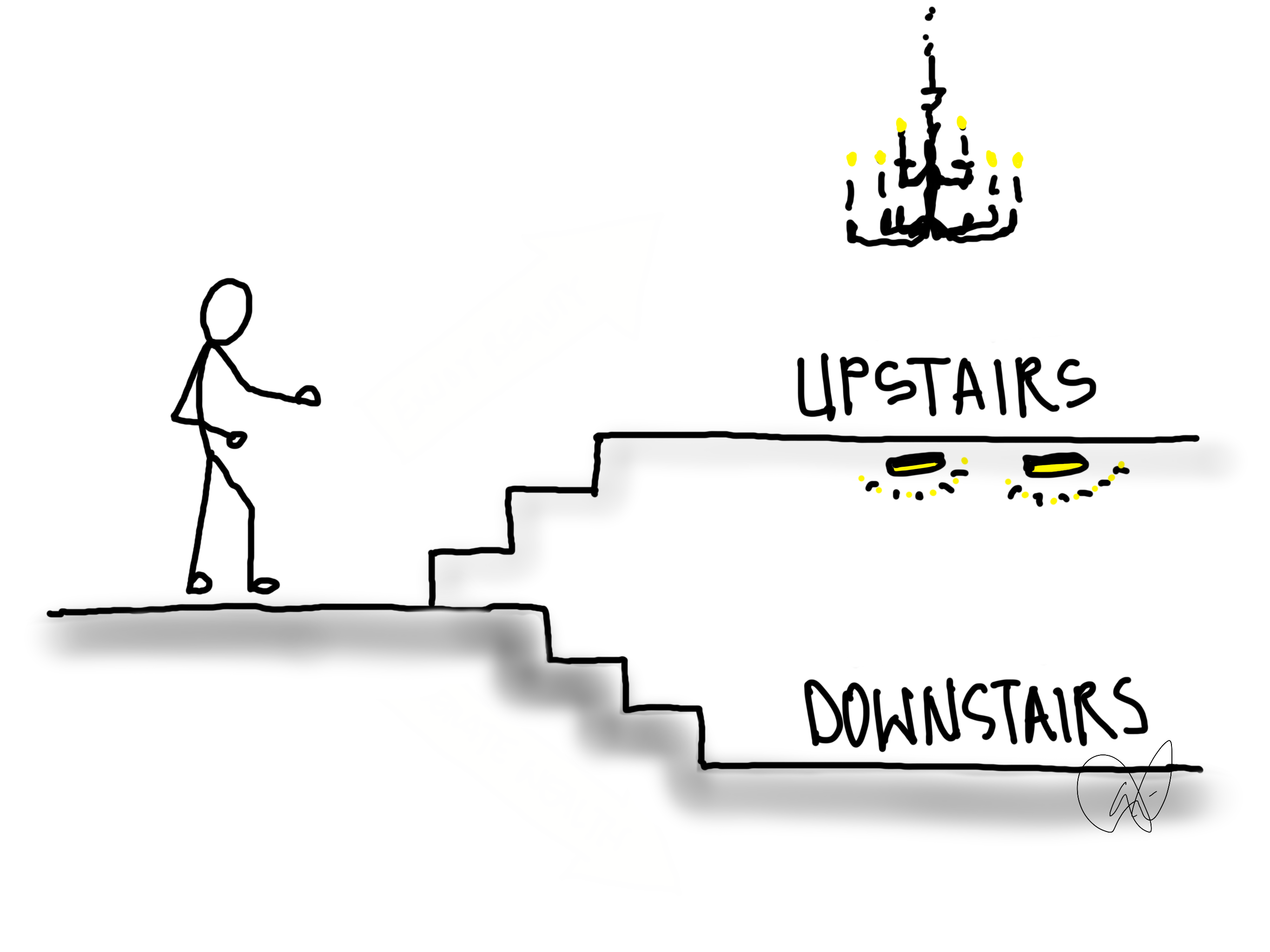

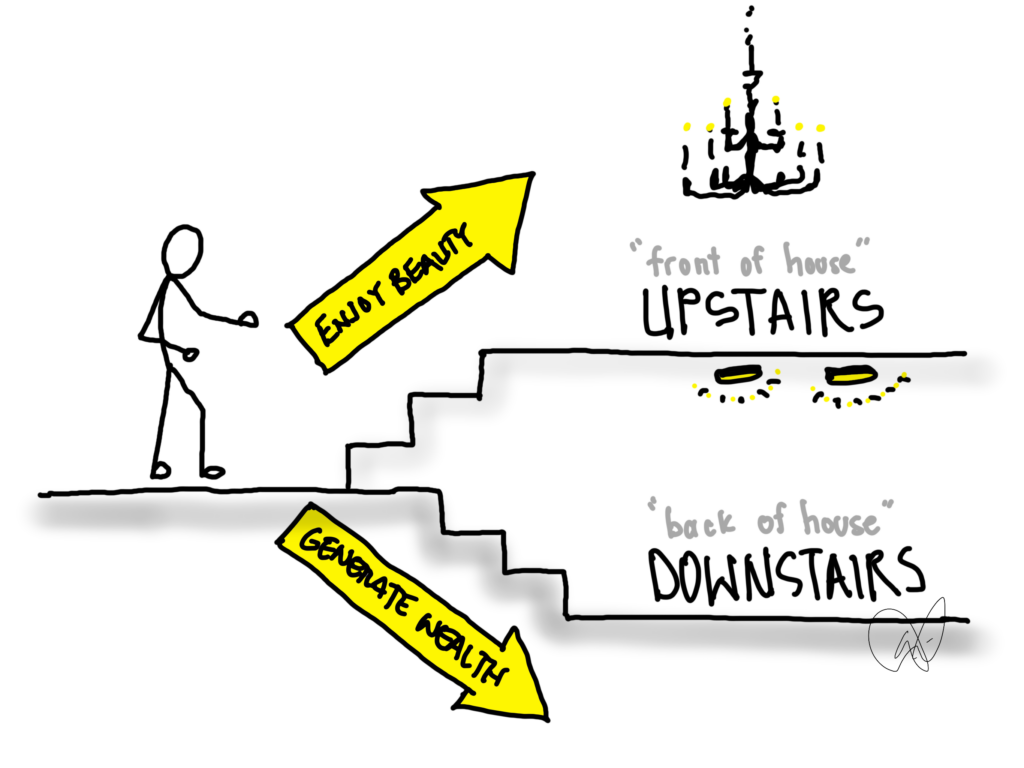

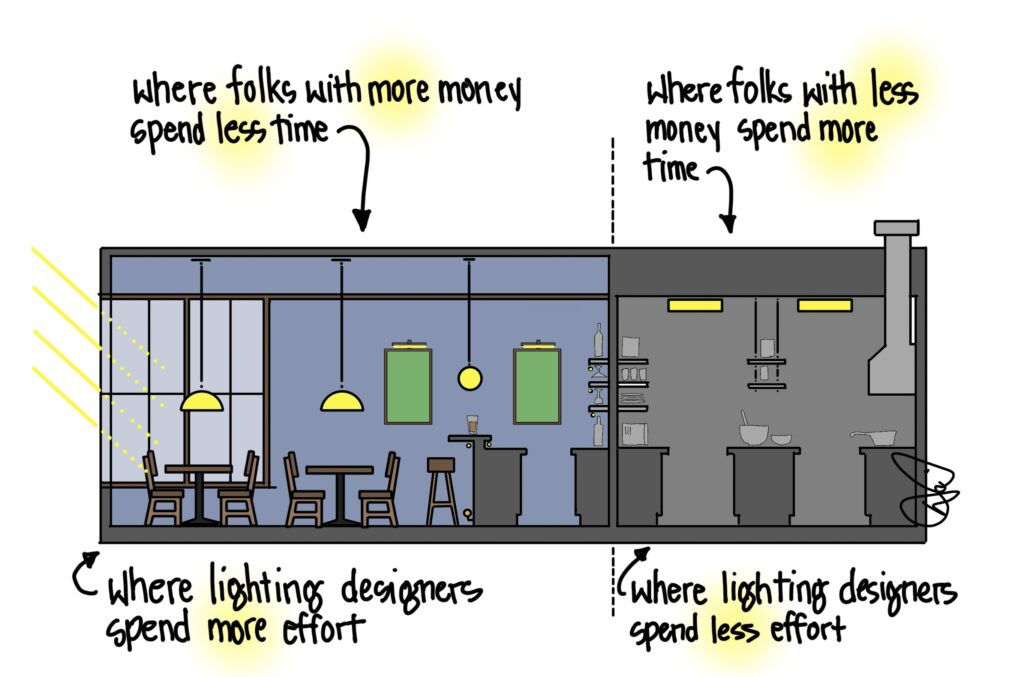

The Light + Justice session laid it out clearly for me to see: I, as a lighting designer, support a modern upstairs/downstairs duality cleverly disguised as “front of house/back of house.”

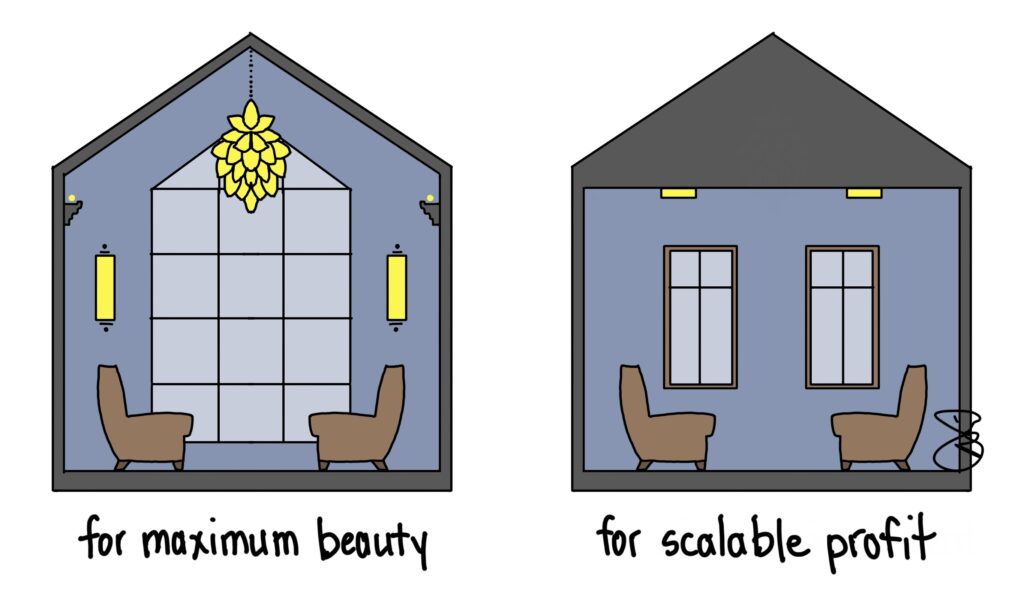

Simply put, Upstairs or Front of House Lighting is designed to exceed code and provide something more, something beautiful, a best-possible experience for the occupant. Downstairs or Back of House Lighting is laid out to minimize energy usage and installation costs, thereby enabling economies of scale that raise stock values. But this split in the industry is not just visible in the houses of the ultra-wealthy.

Inside the walls of the production-built home, you will find very little architectural lighting. What is included is likely disk lights and a few trendy (but poorly functional) decorative pendants. Thousands and thousands (millions, really) are built every year in this style. The entire house is “downstairs.”

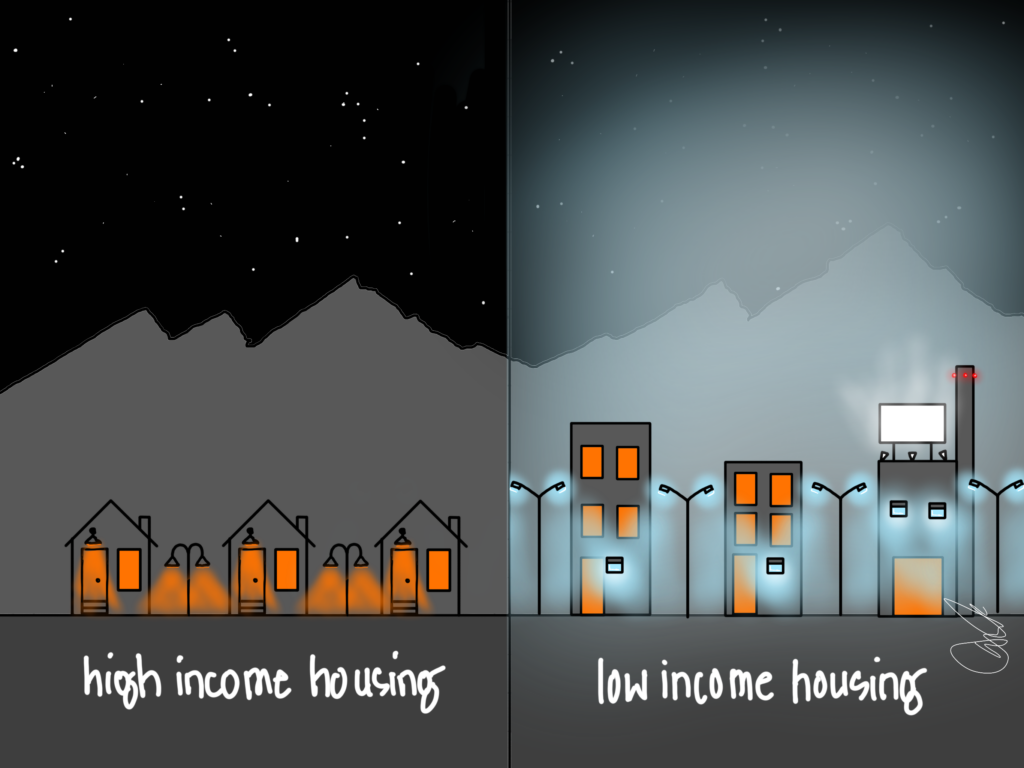

Outside, neighborhoods for the advantaged are more likely to have strict lighting ordinances that protect beneficial darkness, minimizing light pollution and trespass. The results can include better sleep, better health, and more natural beauty. Across town, the disadvantaged live surrounded by higher levels of light pollution that threaten sleep and all but obliterate the stars. We know now how important darkness is, but few of us actually have it.

I usually blog about residential lighting, but I have also designed numerous commercial, institutional and hospitality projects that embody the same unjust treatment. I have designed restaurants where the people who spend the most money and the least amount of time have the best lighting, while those that may work a ten-hour shift lack any natural light and work beneath the cheapest possible artificial light. I’ve done schools where the entry hall, commons area, and maker spaces have great lighting, yet the classrooms barely get by. I’ve walked through many hospital lobbies underneath $15,000 pendants and walls of glass and watched as the nursing staff works underneath $50 fixtures without a window in sight.

Why should we care about light and justice at all? If we collectively support the scientific discovery of the last few decades, then we believe that too much light at night and too little light in the daytime causes harm, even shortens lives. Many of us believe that human productivity and wellbeing can be negatively affected by the wrong light. Many of us believe that too much light is contributing to planetary degradation. Many of us believe that light can help us heal faster, or score higher on tests, or reduce the symptoms of aging. If these are true, then they are true for everyone on the planet. And that is reason enough for us all to care about helping others with light. But we may need to take a hard look at ourselves and our industry and join a dialogue for meaningful change.

Delivering better light for all won’t be easy.

We may even need to change the way we think about our entire industry.

When I entered the lighting design profession several decades ago, I absorbed what seems to be a central tenet of our industry: lighting designers should profit only on their expertise and time, never on product. As I understand it, prohibiting ourselves from selling fixtures avoids the potential of mistrust with the public. I was- and still am- proud to tell my clients that they can trust me because it makes no financial difference to me if I specify one ten-dollar fixture or a hundred hundred-dollar fixtures. On the surface, this is a solid requirement to protect the value of our profession and the integrity of its members.

Yet this belief may also strengthen the divide between upstairs and downstairs, between the wealthy and the poor. A designer abiding by this rule can only really help those with the means to pay a consultant, and that dramatically restricts the designer’s client list. Of course, a designer could choose to donate their services in a pro bono fashion, but this relegates the receiver to the charity column. Justice, at least as I understand it, is not about charity. It is about equity.

If a designer decides to profit from the sale of the fixtures, which is likely the only revenue stream available in lighting for lower-cost projects, they may be shunned by our profession. This model is still relevant and viable- indeed it is how our company survives- but it may be time to look for a third way between elite work and charity.

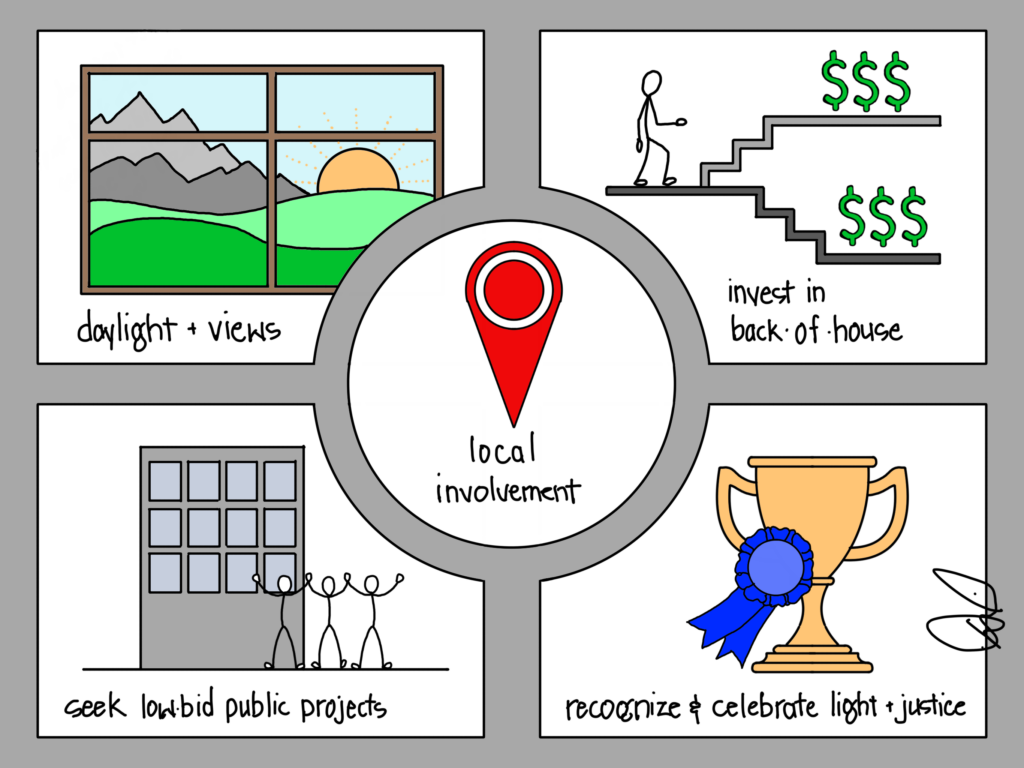

The solutions proposed by Bartholomew, Loeffler, and Osborn point to a new way of light and include providing daylight and views to those who live and work in lower-cost housing or spaces, investing in electric light equally throughout projects, seeking low-bid public projects for our practices, recognizing and celebrating projects that fight injustice in addition to the showstopping big-budget projects, and investing in local organizations and our neighbors.

I would add that industry-wide change may benefit the most people and could be achieved by engaging the public (instead of baffling them with acronyms and metrics), simplifying the process and product (to make better lighting possible without a smart phone or electrical contractor), and building a new professional model (that makes it possible for every project to benefit from the skills of designers and lighting experts). Combine all of these together and we could change the lives of billions of our friends, family, and global neighbors.

We can help more people with light, if we challenge our assumptions, shake up our institutions, redesign our products, and work for light and justice for all.

Read more THINK LIGHT posts HERE.