I just spent the better part of eleven months detailing how light can help us live better lives when we pay attention to the five (or six) promises of light. When I started the series in January, I imagined myself patiently exploring each promise and laying out a strong case for their use in guiding lighting design strategies.

Then I got lost a bit along the way.

There seems to be nothing particularly wrong with my understanding of how light can help us do better, know more, feel better, focus clearly, and change easily. Yet knowing the promises – even knowing them well – does not make it too much easier to obtain these promises. Halfway through the year, what I thought was a whole new language of light tumbled out of my brain and into a slide deck. That is both the challenge and beauty of developing a language of light- languages change and grow as our knowledge and understanding grows.

Since this blog is a chance for me to try out ideas and concepts, I figured I would end the year trying out yet another new organizing structure. And, true to form, I am thoroughly enjoying exploring this shiny new language to the point of neglecting the old. That is who I am, a dreamer of sorts, a person always seeking the next idea. For a brief moment, I thought this new language would replace the older language I have been detailing all year. But as I discovered (and will share in the next series post), this new language compliments, rather than conflicts, the previous language, like Spanish being built on top of ancient Latin. Different…yet inexorably connected.

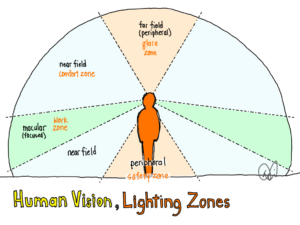

Last year I wrote a post on human vision exploring our field of view that includes foveal & macular vision (the focused part at the center of our view), near field, and far field/peripheral (out of the corner of our eye, as it is said). These are not my ideas, but simply our current scientific understanding of the human eye and our vision. This is a great place to start for a language of light, because every photon we see- and every photon that affects our mood and body clock- comes into our bodies through the eyes.

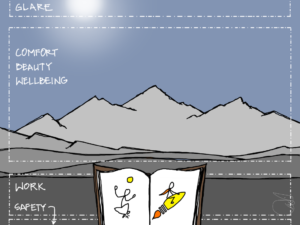

It took me awhile to realize that these zones of vision could directly guide us when planning lighting for human wellbeing. Our peripheral field of view, dominated by rod cells, is our more light-sensitive zone; therefore it is also highly susceptible to glare. Our near field, by far the largest area of vision in our consciousness, also hates glare. But this zone can be very comfortable when it is filled with soft light. Our macular/foveal vision, the part of our vision you are using to read these words, needs good strong light to increase our perception of the tiny differences between the letters i, t & f. Down below us, where we walk, our peripheral vision needs subtle glare-free light for safety.

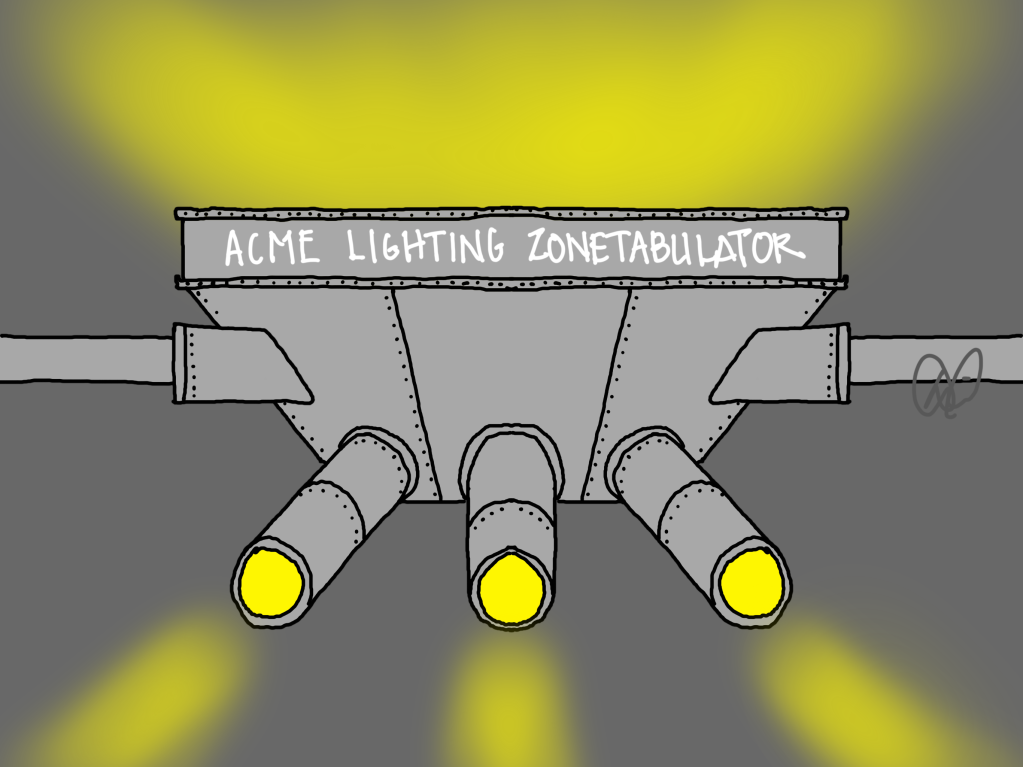

Once I began exploring zones of light, a whole new level of language clicked into place.

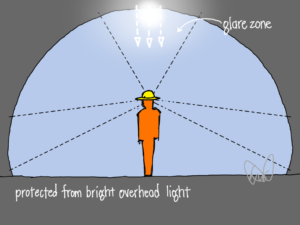

Let’s start with the glare zone, the portion of our peripheral vision directly over our heads (and out to the far sides of our vision). I am calling this the glare zone because we really do not want strong light pointed at us in this zone. Think of a sunny summer day; many of us prefer the shade of a tree or a hat to being pelted by direct sunshine (unless our eyes are closed). Our bodies were made to protect us from this kind of glare; our eyes are sunken back into our heads perhaps in part to give us built-in sunshades. When we have to have that kind of light, like on a professional football field, we paint the tops of our cheeks with black paint to limit the light that reflects back into our eyes.

In other words, we don’t like it. Yet this is where most lighting in our homes and workplaces lives: directly overhead in our glare zone.

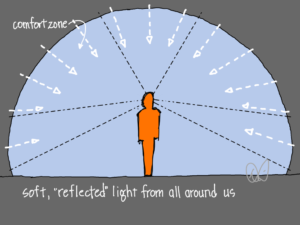

There is a sweet spot of vision directly in front of us. This near field is where we watch sunsets, where we put our windows, where we see the faces of our loved ones, where we admire art, even where we watch movies. Outside, this comfort zone is filled with soft light reflected off trees or mountains or refracted through the atmosphere to appear as a bright blue sky. Our bodies are built to take this light in and use it for more than just vision: this light also impacts our mood and circadian clock.

In other words, we love it. Yet this is where our homes and workplaces are often the darkest.

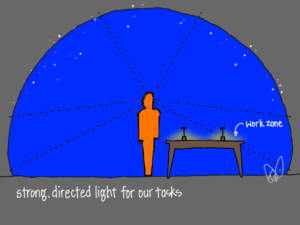

When we are outside on a sunny summer day, we do not carry flashlights. It would be foolish to take a desk lamp outside on such a day, a waste of electricity and effort for likely zero return. Indoors, walls and ceilings block out much of the beneficial daylight and we supplement with electric light. Our work zone, located where our near field of vision intersects our hands, can benefit from strong directed light while our eyes want to be protected from glare.

In other words, we need light directed here. Too often, our homes are filled with fixtures that direct light into our eyes or nowhere at all.

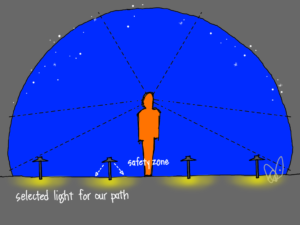

The final zone of this new approach to light is also in our peripheral vision yet down below our eyes instead of overhead. During the day, this zone is filled with light and we do not need anything dedicated to it. At night, however, we can protect our sleep and our eyes when we selectively place lights that softly illuminate the path. We still need to protect this area from glare, so pointing lights away from our eyes makes sense.

In other words, we need light for our feet that is not above our heads. Yet most homes have no light down low and even the most common path lights put as much light into our eyes as where we need it.

Look out ahead of you. That is the comfort zone. Is it filled with soft light from a window or a screen? Will it be filled with soft light after the sun comes down?

While still looking ahead, pay attention to the glare zone above your head. Can you see brightness on your eyebrows or eyeglasses? When you turn that light off, does it feel more comfortable on your eyes?

Now look at your hands. Is there light available where you are cooking, typing, knitting, or reading? Is it shielded, directed away from your eyes?

Tonight, walk through your home. Can you navigate safely without turning on overhead lights? If not, where could you put light down low in selected locations for safety?

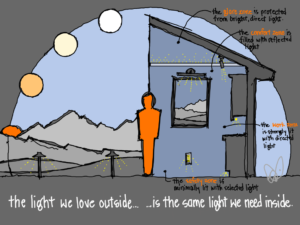

I have been a lighting designer for twenty-five years, learning the entire time, and there is no way I will ever master every aspect of light. Lighting design is a highly specialized, artistic, technical, and detailed profession that requires years of training and/or experience. Yet we all know what makes good lighting: a beautiful sunny day, a gorgeous sunset, a star-filled night sky with soft path lighting.

We use the same eyes outdoors and indoors, but our lighting inside usually ignores our vision for the sake of convenience and cost. Our glare zones are filled with bright overhead lights and recessed downlights pointing in exactly the wrong place. Our comfort zones are dark, our walls and ceilings lacking after sunset. Our work zone may have light, but it usually comes from the glare zone and threatens our sleep and wellness. And down below our knees, where shielded light in select locations would help us navigate with ease, we experience either darkness or light coupled with overhead glare.

The light we love outside – that our eyes are built to consume – is the same light we need inside. And that pretty sums up the goals of my career.

Read more of my Light Can Help Us series HERE.