“We don’t want any recessed cans in our home.”

Architects, interior designers, and homeowners occasionally tell us they do not like recessed can lights in their projects and homes. My habit is to get defensive, to fight back, to draw upon decades of lighting design experience to tell them why they do want recessed cans in their homes. Upon reflection, this may simply be a language translation issue. Here’s how I might answer the question the next time it comes around:

“I don’t want to use any recessed cans, either.”

Why would I turn my back on this ubiquitous piece of equipment? Because I hate sporks. Let me explain.

The spork is an eating utensil with tiny fork-like tines, a spoon-like bowl, and sometimes a knife-like edge. It is someone’s creative attempt to create one utensil to rule them all, to eliminate the clutter of spoons, forks, and knives at meals. Perhaps it was an altruistic creation, an environmental move aimed at reducing plastic utensil waste after the church potluck or outside the barbecue joint. Whatever the reason for its existence, there is near universal agreement that the spork is…nearly useless.

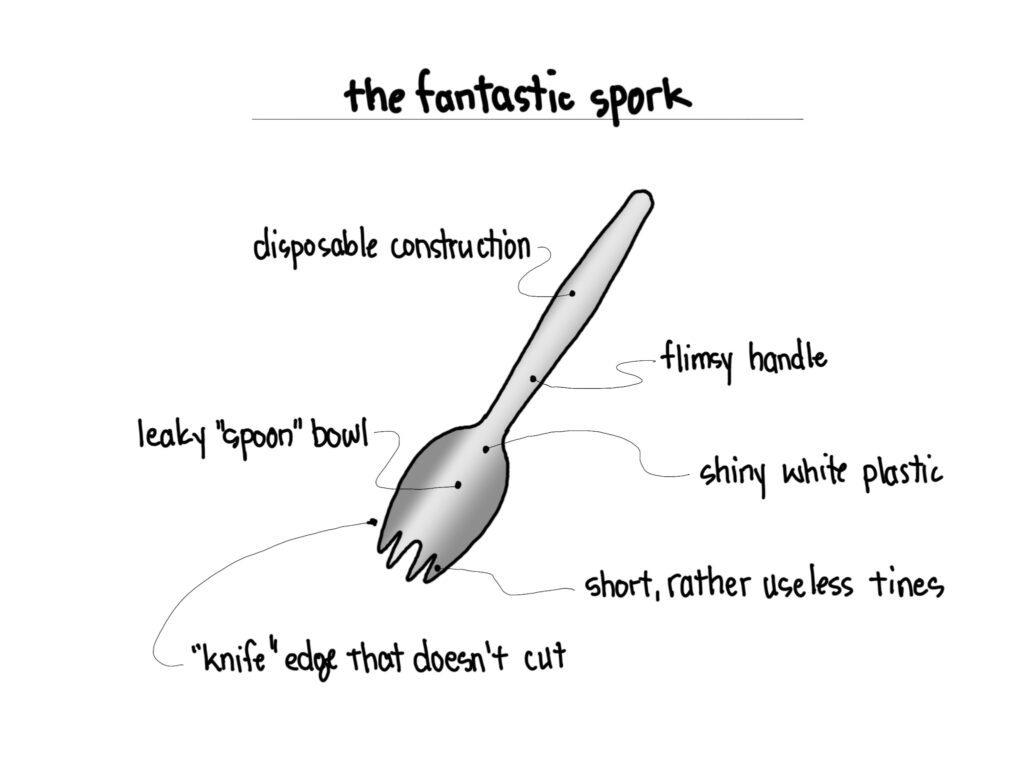

Nearly every spork I’ve seen has been cheap plastic, a disposable item manufactured not for durability but for maximum profitability. The handles snap the moment you hit anything tougher than overcooked pasta. The knife edge cuts through the styrofoam plate but little else. The spoon bowl has leaks built in and the fork tines are so short that picking up anything is nearly impossible. The spork does absolutely nothing well.

Just like a recessed can.

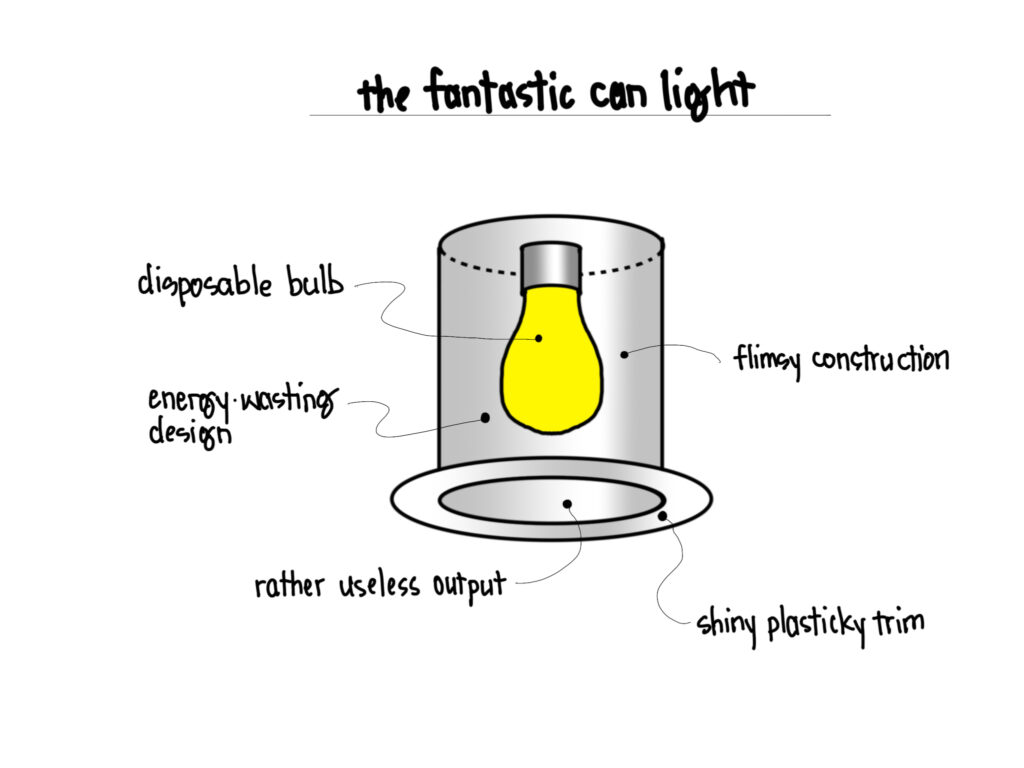

The popular recessed can light has more in common with a spork than a well-made steak knife or dinner fork. The recessed can is cheaply made – for the price of a burger and fries, you can pick one of these up at your local big box home improvement warehouse – and wastes energy and light as a result. The cost is kept low by utilizing a 100+ year old screw-in base that forces you to use disposable bulbs. The trim – the piece you see below the ceiling – is just as cheaply made and is a little like glueing plastic sporks to your ceiling. Nobody wants that.

Even worse, for a lighting designer who cares about light, the recessed can is a terrible deliverer of light. Many lumens are trapped inside the can (cans are for storage, after all) and those that escape tumble lazily to the carpet below. Recessed cans do produce light, but it is the wrong kind of light in the wrong place.

You might call it a recessed can’t light for greater accuracy.

Here’s how to spot a recessed can in the wild: look for 4, 5, or 6 inch holes in your ceiling. Look for nice tidy grids and straight rows of circles that spill light onto your carpet. Look for screw-in disposable bulbs made with cheap LED components.

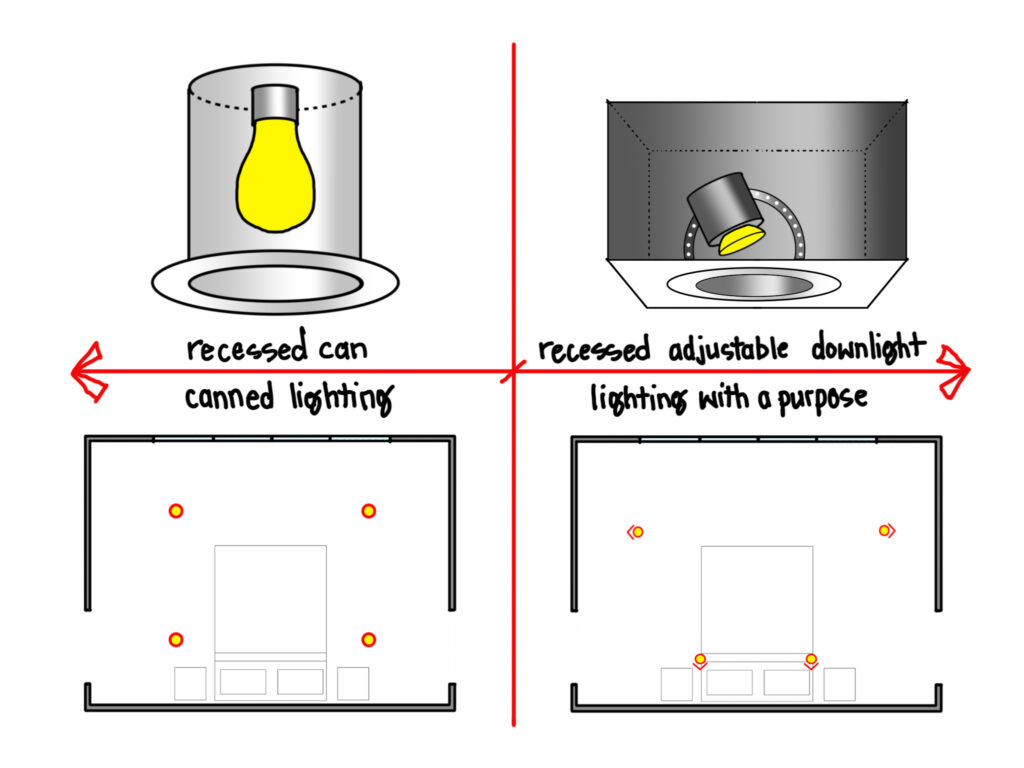

If you find something else in your ceiling, a light fixture with built-in high-quality LED components, a recessed light aimed at art or walls or counters, a fixture with a cast aluminum trim that snugs up tightly to the ceiling, a layout of fixtures based on walls instead of floors, you may have discovered the recessed adjustable downlight.

You could be forgiven for thinking this is just another recessed can. From below the ceiling, they can look very similar, like a spork and a spoon. Hold one in your hands, however, and you’ll feel the difference immediately. And try to use a recessed adjustable downlight (or spoon) and you’ll have far better luck than if you try to use a recessed can (or spork).

We use recessed adjustable downlights by the hundreds in our projects because they do different things than recessed cans, and that is a very good thing.

So the next time a client tells me they hate recessed cans, I’ll agree with them. And then I’ll introduce them to the recessed adjustable downlight.

Read why downlight size can be a red herring.