Light is so awesome that I occasionally need reminded that light is not everything. The human experience- in nature, in buildings, with others- is affected by so many variables from the particles in the air to the temperature around us to the views outside…and by what we ate, how we slept, who is nearby, what happened yesterday, and what we fear may happen tomorrow.

In other words, light is no miracle cure for all of life’s ailments. But light is a miracle, and it can help with many of life’s challenges. One such challenge is how to stay focused on what matters most.

One of the basic tenets of theatrical lighting is the “brightest spot in the room” metric. Over and over, my mentor asked me “where is the brightest spot on stage?” If I answered “the chandelier” or “the upstairs balcony,” she would then ask “is that where it should be brightest?” We all knew, if she asked the question, that we were drawing attention away from where it was supposed to be.

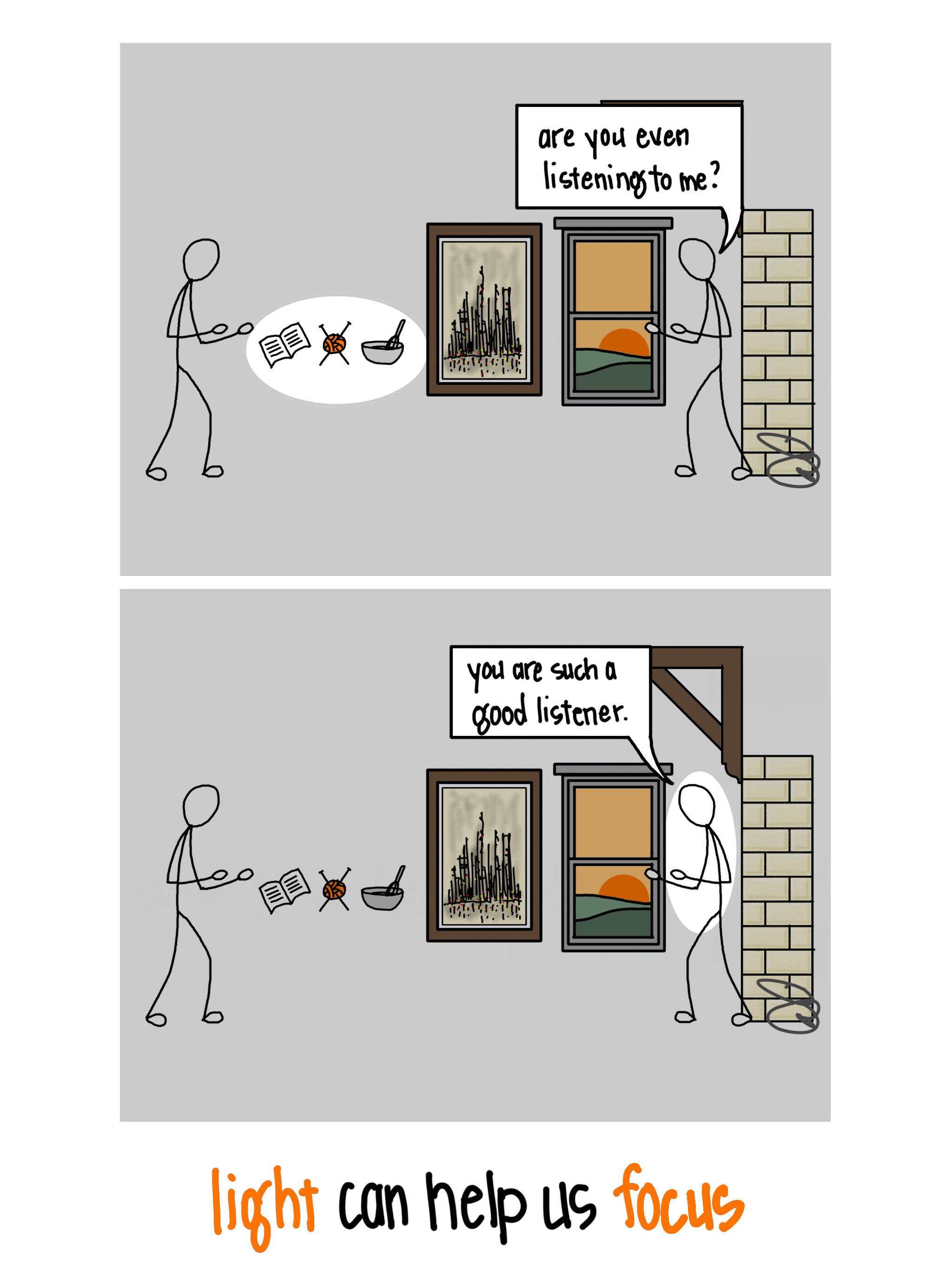

We are biologically driven to seek out light and focus on the brightest spot in a room or on a stage. This is one reason that followspots are used in concerts and musicals. Not just so we can see the star performer, but so we are compelled to look at them. A theatrical lighting designer is deciding where you will be looking before you even buy a ticket.

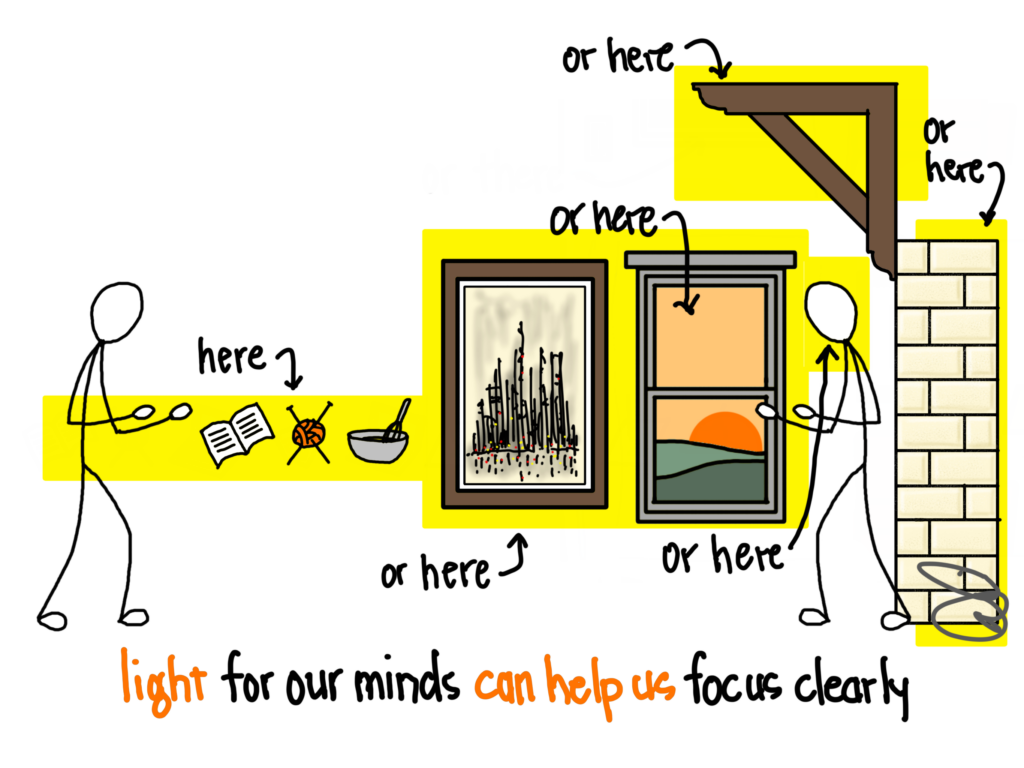

Life may not be a performance with an orchestra playing underneath us, but we are still attracted to light when we leave the theater and go home, to dinner, or to work. In our daily lives, light for our minds can help us focus on what is important to us. There are two concepts that help us plan for this: contrast and choice.

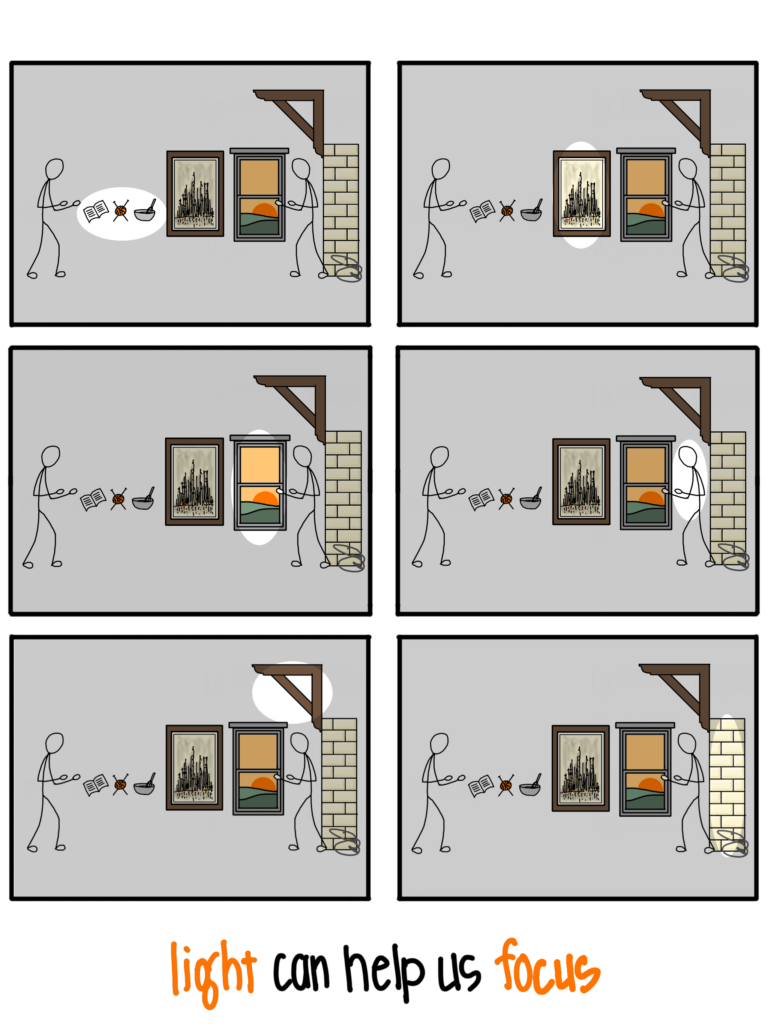

Choices must be made to put the power of light to work for you, choices about what you are doing and where you want your attention to land. This makes light for focus a little bit harder to grasp than some other layers, like light for our feet, but it invites you to stop and think about where you want to invest time, attention, and light.

- This may include tasks performed with your hands like reading, knitting, or cooking. Imagine that you are trying to read a book in adequate light while there is a bright light shining on something else. Your eyes will constantly be pulled away from the book, subconsciously, making it more difficult for you to read, learn, or enjoy the book.

- Light that helps us focus clearly can also be used on artwork on our walls, whether that be a priceless original discovered abroad or a collection of family photographs. If you want to fully enjoy what you hang on your walls, it needs to be lit.

- Sometimes we want to focus on nothing inside but let our views of the outside draw our attention. This also requires thought for lighting. If it is daytime or dusk outdoors, then we can make that the focal point if we carefully dim our inside light. With a bright indoors, outside will look dark long before it actually becomes night.

- Architectural details in buildings can be beautiful, elegant, and key to appreciating the space, but often they are left in the literal dark. If we want to focus on a particular detail, like a beautiful crown molding, it needs to be lit.

- Theatrical lighting designers, above almost all else, are concerned with lighting the faces of the performers. We usually make these the brightest spot on stage, subtly dimming the backgrounds until the faces are front and center. We seldom think of this as architectural lighting, often more concerned with task light or accenting details, but providing good “face light” can help us focus on our companions. This light also helps us know more and is part of another post.

- Sometimes the walls themselves are worthy of focus. Interior designers and architects carefully choose what covers our walls, whether it be simple paint, complex textures, stone, tile, or wallcoverings. Good light on those walls, textures, and finishes can help us enjoy them more.

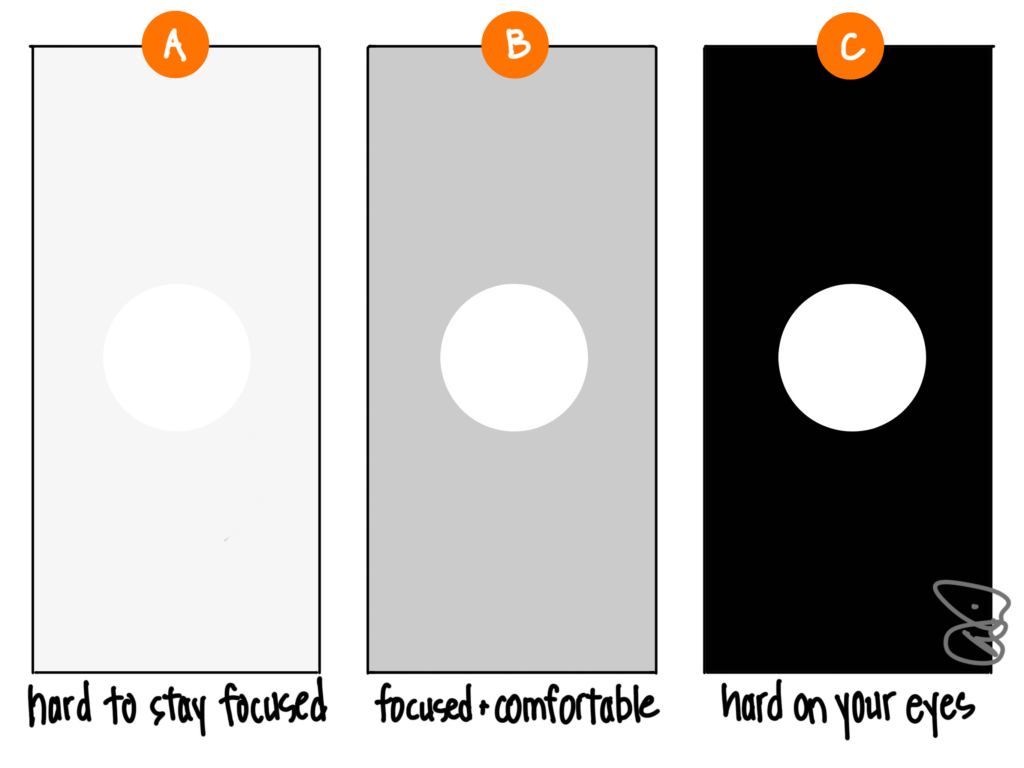

After we choose our focus, it is time to consider contrast, the key concept of focus. Lighting geeks like me talk about contrast ratios, essentially the comparison of “brightness” of one object to its surroundings. It turns out that most humans prefer a little bit of contrast- it is what makes a sunny day unique and what makes stacked stone most beautiful. There are a few rules of thumb to planning contrast, but the general idea is a lot like Goldilocks and the Three Bears: look for “just right.”

- Too little contrast makes it difficult for us to focus in on the task, face, art, or other important item. When everything is illuminated evenly, we have put ourselves into a situation not unlike a cloudy, overcast, rainy day.

- In the middle is a nice amount of contrast that provides a clear focus but is easy on our eyes as they adapt to our surroundings. I often hear 3:1 as the desired contrast ratio (your art, for example, should have three times as much light as its surroundings), but that needs to be taken as a guideline and not a hard and fast rule. Good controls are often needed to get this just right, which I hope to dig deeper into later.

- Too much contrast and our eyes don’t know whether to open or close our irises, and over time this can hurt. High contrast might be okay for a concert, but extended comfort requires a careful balance.

Choice and contrast, when used together, can draw the eye anywhere we want. That allows us to focus on a task at hand, or a detail, or a face…there is no right answer but the one we choose. Light for our minds can help us focus on what is important to us, and that helps us live better.

Read more of the Light Can Help Us series HERE.