History and literature are full of great tales of adventurers seeking the unattainable. There is the quest for the Holy Grail (“We’ve already got one.”), the search for the fountain of life (find it or die trying), and the hunt for Blackbeard’s treasure (he spent it on rum, I think).

Right up there with the most notable quests is the search for a decently-performing, easy-to-install, and moderately priced recessed downlight. I’m pretty sure that the ancient Greeks wrote about this in an epic poem, but it got lost in the washing machine. I guess it’s up to me to continue this most noble of tasks. I suspect the results will be the same as the other great quests.

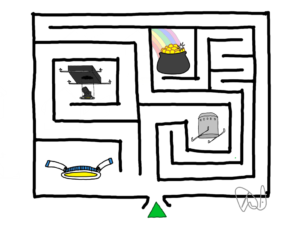

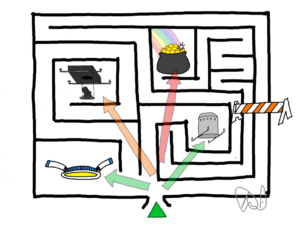

It is, admittedly, rather easy to find a great downlight. There are some very high quality manufacturers out there building performance fixtures that meet the demanding requirements of a professional lighting designer. It is even easier, sadly, to find a terrible downlight. Just go to the nearest big box retailer and you can fill your cart and be out the doors in minutes. But where is the pot-of-gold fixture in the middle?

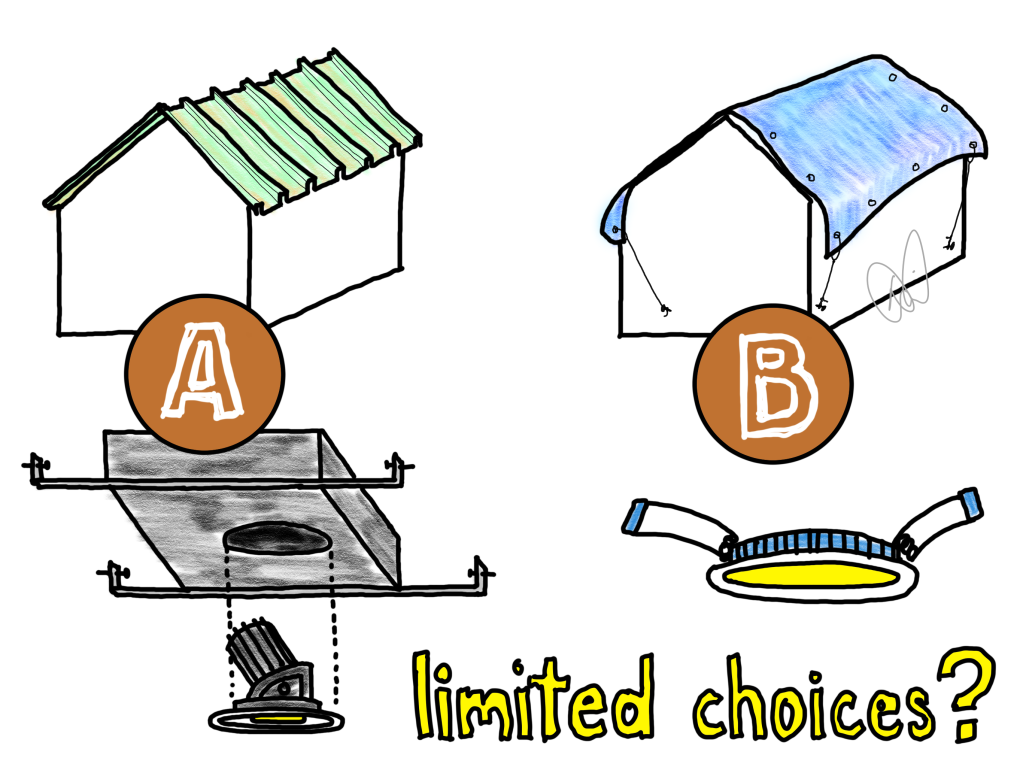

It’s a good thing that other building materials do not suffer the same “missing middle” effect as lighting. Imagine a world where there are only two roofing options: hand-built custom copper roofing and blue tarps held down by bungee straps. One would be prohibitively expensive for all but a small fraction of homeowners, the other easily affordable but terrible in performance.

That is not too far from the reality facing most residential projects. There are great downlights affordable to a few, but most homes are built with wafer or disk lights that cost as much and perform as well and last as long…as a blue tarp and bungee cords on a roof.

Why?

When I tackle a question in the blog, I usually have an answer in my head before I begin writing. But, in no small percentage of cases, I may come to a different answer through the process. I may start out ready to rail against some corner of our industry (It’s because manufacturers are greedy! Builders are lazy! Lighting Designers are geeks!) but end up finding a more nuanced and sympathetic view.

That happened today when I wondered aloud “why do there seem to be no middle-class recessed adjustable downlights I can use on projects with more moderate budgets?”

The primary reason, I suspect, is that few people know how helpful, functional, and beautiful light can be. If you do not believe in the Holy Grail, there is little sense in looking for it.

A second reason, perhaps, is that finding such a light fixture takes time, and time takes money. This is important for discovering the roadblocks that keep us from moving to a better future.

Builders and electricians should not be blamed for choosing inexpensive, easy to install wafer lights instead of pricey, difficult to obtain, performance downlights. The blame should sit squarely on the shoulders of us, the lighting industry.

Imagine you are a builder or electrician on a typical residential project. You are tasked with purchasing and installing recessed lights throughout a house, more-or-less as laid out quickly by someone else simply to meet permitting requirements.

Should you sit at the computer for a few hours, spend a few more hours meeting with manufacturers, perhaps visit a factory or two, order samples and test them out? Or should you go to the lighting supply house, ask for 150 2” LEDs, and pull the truck around back?

Lighting designers like me can spread the cost of research and testing out over numerous houses, patiently seeking the perfect recessed downlight. We, unlike electricians and builders, are literally paid by the hour to do so. It is our job.

But because we are paid by the hour, and it takes a lot of hours to do a custom lighting design, most homeowners can never afford our services. This creates a vicious feedback loop – it would take us hours and hours to find this miraculously affordable downlight, but our clients have plenty of money, so why not go with the $750 version? This decision, made over and over by the specifying community, effectively removes any and all motivation for a manufacturer to offer something in between.

On one side are builders and electrical contractors, tasked with keeping prices low, who have every reason to purchase and install the lighting equivalent of a tarp over the roof. On the other side are the lighting designers, tasked with providing the best light, who have every reason to specify the lighting equivalent of the handcrafted copper roof.

In the middle is you and me, and most other homeowners and renters.

So is it any wonder that most choose the easy route through the maze, the quick path to low-cost recessed lights? Is it any wonder that only the highly paid consultants might find the proverbial pot of gold…but because they don’t have a compelling reason, the road falls into such disrepair that eventually there is no path left?

I wanted to write something helpful, but that is not where this ended up. Instead, I am asking all of us to do something different: to build, specify, and install more middle-class downlights. We have the knowledge, we have the technology, we have the distribution systems to do just about anything. Downlights that meet the criteria likely already exist though “reasonably priced” is a statement bound to garner strident disagreement.

So let’s find this: a recessed adjustable downlight with at least 30° of low-glare tilt, interchangeable optics, replaceable parts, air-sealed housings, in warm-dimming, 1% or lower dimming, high-CRI, and easily purchasable for $100-$150.

A lot of folx will be better off when we find- and use- this fixture.

If you have a fixture you think fits these criteria, I would love to hear about it! Perhaps soon we could build a short list of options to share with others.