A few weeks ago I got to geek out a bit with some lighting colleagues during dinner, a rare treat for someone who works mostly remotely. My Zoom conversations are almost always task-oriented, designed to accomplish something and then move on to the next one, and that makes unscripted, unmeasured, non-billable communication somewhat unusual- and somewhat wonderful.

The conversation rambled through a number of topics but circled back a few times to human centric and circadian lighting. These two terms are sometimes used interchangeably (I confess to doing that myself), but one of my colleagues (thanks, Mark M!) encouraged me to think about them a little more deeply. What is circadian lighting? What is human-centric lighting? And why should we care?

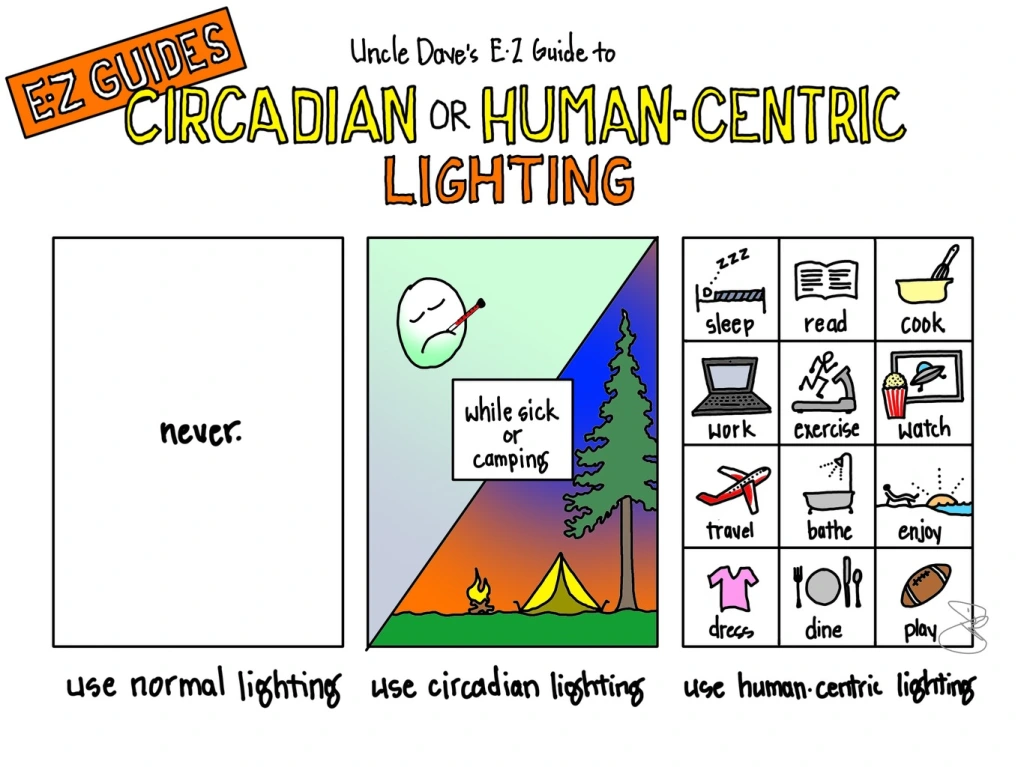

First of all, let’s establish a baseline which we can call “normal lighting.” If you have read any posts on this blog, you are probably getting tired of me calling out the pitfalls of the ubiquitous bad lighting in our homes and workplaces. We have dumbed it down, drained it of life, and oversimplified until we arrived at our current state of fixed white light all day every day. In other words, we took light, stripped it’s beauty, magic, and health benefits, and then pushed the freeze button to make sure it never changed. This is our current normal. If you have more light switches than dimmers, if you use LED bulbs that do not have warm-dimming functions or better, if you have chandeliers with visible light bulbs, you suffer from normal lighting. I’m sorry. There is a better way.

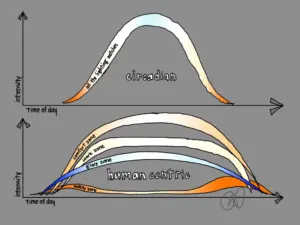

Circadian lighting is definitely not normal. I am going to define it- for my own use- as lighting that is fully synchronized with daylight. When the sun rises, circadian lighting turns on at a bright warm glow. When the sun hits the middle of the sky at noon, circadian lighting is at its brightest and bluest. As the sun moves lower on the horizon, circadian lighting begins to dim and warm towards sunset. And when the sun is set and the sky is dark, circadian lighting is turned off and completely dark.

In other words, circadian lighting is natural lighting, electrified and brought indoors, fully synchronized with what is happening outside. For a few years, I thought this was the ideal solution to lighting problems. I advocated for apps that continually monitor local time and solar conditions and adjust lighting to match. I praised control systems and lighting technologies that synchronized color temperatures of all the fixtures to match daylight. I designed homes on the forefront of this concept.

Then I saw the results and was instantly and deeply unsatisfied but could not immediately put my finger on why I disliked circadian lighting so much.

I know now why I disliked those early adoptions of circadian lighting, and the answer is somewhat complicated and at the same time simple: synchronization with daylight does not work well for our societal needs and unified color temperatures are like living in a sepia-toned photograph from the late 1800’s. Neither puts a particular value on the needs of the humans living in the spaces.

Enter human-centric lighting. This admittedly nebulous term can mean a number of things, and I suspect there are professionals and researchers out there who can do a far better job than I at constructing reasonable and accurate definitions. I, on the other hand, just want a definition that is simple enough for me to understand and put to use.

Human-centric lighting, to me, is a careful balance of our bodies’ biological need for natural light and our societal demands for increased productivity and extended play. Human-centric lighting mimics, without strict adherence, the rise and fall of the sun and the passing of seasons, while giving us enough light to do what we need to do even after sunset. And human-centric lighting recognizes our desire- perhaps our need- for dynamic variety.

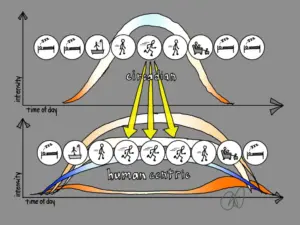

If circadian lighting brightens when the sun rises, human-centric lighting brightens when we rise, effectively making sunrise happen on our schedule instead of the universe’s. If that sounds pretty human-centric, well, that’s the idea. Personally, I would love to wake with the sun and go to sleep with natural darkness, but there are good portions of the year where that would make for very short days and very long nights. If I lived with circadian lighting in the Wisconsin winter, I would wake around 8am, show up for work about 10am and clock out around 2pm so I could eat dinner, finish my chores, and go back to bed around 5pm. My schedule would be a little bit different every day, depending on weather and the continual change of natural light, and that might make it hard to schedule meetings. Given that I am, in this scenario, working a four-hour day minus a lunch break, that’s going to make it tough to meet my (self/work/societally-imposed) goals and deadlines.

I would rather have human-centric lighting that begins to glow around 5:00am, gently wakes me without an alarm around 5:30, energizes me from 8am until 5pm, and then gradually dims to prepare me for sleep around 9:00pm.

Enough Light for Now

We need light to see what we are doing, and that can mean anything from shaving at 6:30am to reading a book at 9:00pm. Circadian lighting doesn’t care what light we need to for task, it simply cares about what the sun is (or is not) doing at a particular point in time. For the same reasons listed above, this does not work very well for human lifestyles. For centuries, for millennia, we have fought against the limitations of natural light. We burned fires, then candles, the oil lamps, then electric lamps to help extend our usefulness past sunset. In some basic sense, all electric light is human-centric in that it is created for our use. But the definition breaks down quickly if human-centric is something more than “having enough light to do something,” if human-centric also includes allowances for what our bodies need. And our bodies need more than just enough light to see.

Dynamic Variety

Circadian lighting, at least the variety that carefully matches all color temperatures in a space and synchronizes them with sunlight, looks pretty ugly to me. What took me literally a year or two to realize is that unified color temperatures look bad because they are decidedly unnatural. Yes, our quest for “natural light” has taken us further from it by stripping out the dynamic variety present in real life.

Dynamic variety, to me, means that we take into account the entire picture of natural light at any given moment. While the rising sun itself may produce extremely warm color temperatures (for example, 2500°K amber), the sky around it is filled with a continuous gradient of very different color temperatures. We see not only the orange sun itself, but also the yellows and golds, the magentas, and the deep blues of the sky itself.

At noon, when we have 7000°K crisp cool white sunlight, our eyes also see deep blue above and paler blues near the horizon. Our eyes also take in green light reflected from surrounding trees and a rainbow of colors bouncing off everything in sight.

All Together

My desire for human-centric lighting can be simplified to coordinate with my attempt to categorize different zones of human vision, as detailed in earlier blog posts. The Glare Zone, the area of our peripheral vision above our heads normally filled with the sky, needs to have soft light reflected off ceilings and walls to simulate the sky, and can be rather cool in appearance. The Comfort Zone, our near field of vision where we see art, landscapes, and the faces of our companions, also needs to be filled with soft light but can be brighter and warmer. The Work Zone, where our hands perform tasks that need good light, can be a bright and more neutral in color to help us work better. And the Safety Zone, the area where our feet tread, needs minimal warm light as we wake and prepare for bed…and as much darkness as possible as we sleep.

Human-centric lighting supports our needs, extending our productivity while acknowledging the biological need for light that is dynamic and varied. The result can be light that helps us live better lives in almost every circumstance. Circadian lighting, which I define as light that careful synchronizes with the sun, is best for camping or when you are sick and need maximum rest. Normal lighting is best for…nothing.

Which will you choose?