“What do you do for a living?” inquired my seat mate on a recent flight.

“I am a lighting designer,” I replied.

[BLANK STARE]

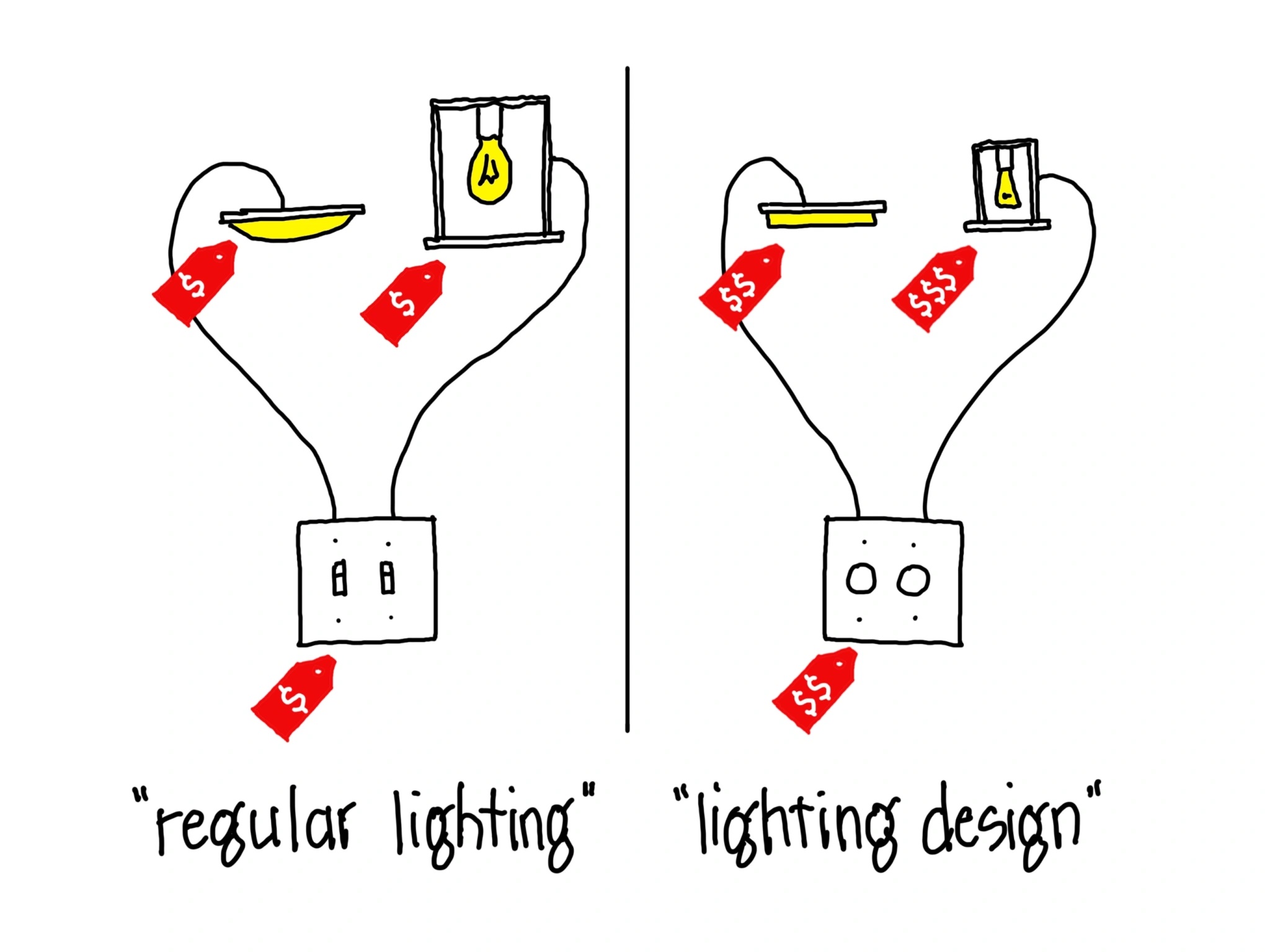

Explaining my job is, well, difficult at best. If people have any awareness of lighting design, it likely falls into the sentiments displayed in the image above. Our lighting plans, so the thought process goes, are the same as the lighting plans provided by the architect, it’s just that everything costs more. The fixtures are more expensive, the switches are more expensive, and so on.

There is some truth embedded in the misperception: our work almost always costs more than what is currently on the plans. We use different fixtures that perform differently. We recommend control systems to simplify daily use. But lighting design is not a one-for-one swap of fixtures on a plan. It is not just a swap for more expensive things.

Lighting design is different in every single way from lighting layout. Lighting layout is circles on a plan, four cans and a fan, nice tidy rows of recessed downlights marching through a space regardless of the wall layout, furniture, art, or, frankly, humanity that will reside in the spaces. Lighting design starts with the human, the occupant, and works in reverse. Instead of putting ceiling geometry first and human biology last, we study light’s affect on the human body and mind and apply the science and theory to a home (or workplace).

“I help homeowners, builders, and architects figure out how do do lighting in homes.”

[PUZZLED STARE]

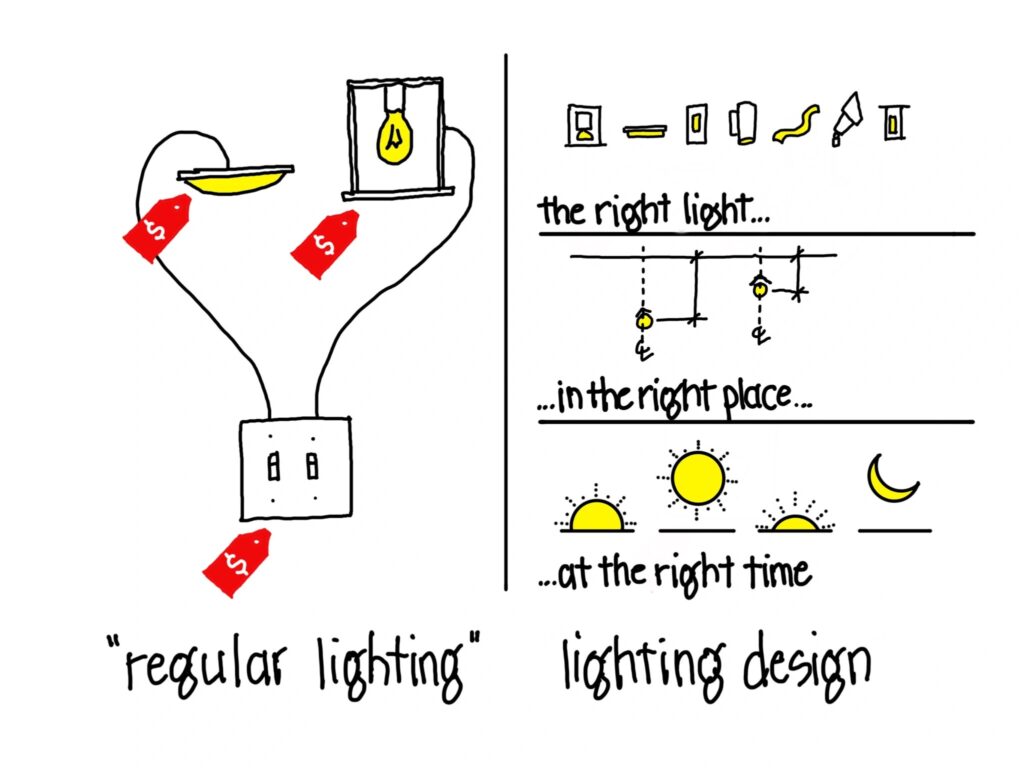

Lighting design can be very complicated to explain, so I did some doodling on the airplane and came up with the sketch above, an over-simplification but also very true. We put the right light in the right place at the right time.

THE RIGHT LIGHT

Lighting designers invest an incredible amount of time in knowing lighting fixtures. We go to trade shows to see the latest gear. We acquire samples for testing in our offices. We run detailed photometric calculations to understand the impact of fixtures in a particular space. We spend time with manufacturers and representatives digging in deeply. We even tour factories where fixtures are made so we can more fully understand their functionality and limitations. Our team spends dedicated time every single week learning more about fixtures, and we have nearly 100 years of collective experience already.

So when we say “this is the light I recommend,” we’re really saying “this is the light from a well-managed factory that is engineered for precision, distributed reliably, with the right photometric qualities to accomplish the goal, that was updated two months ago by the manufacturer, that I had in my office and examined for fit and finish and quality.”

THE RIGHT PLACE

A nice automobile headlight located in the trunk of the car will be great at illuminating the groceries but terrible at helping you see where you go. Sadly, the architectural equivalent is what most homeowners get. You would be shocked how many kitchens have recessed downlights over the floor instead of the countertops, or headlights in the trunk.

Getting the lighting in the right place begins with understanding the human eye and its perception of light. We do not have eyes in the tops of our heads, so what the ceiling looks like is less important to us than how the walls are perceived. Your eyes will be looking at the art on the wall, or the bread on the counter, or the book in your hands, so we’ll figure out how to get light there. We measure ceiling heights and aiming angles. We study cabinet designs and furniture layouts. We build 3D models so we can see the home the way our clients see the home – from the inside, not from above like a lighting plan.

So when we say “this is where the light should go,” what we we’re really saying is “this light should go this many inches away from this wall so that the beam creates a scallop of light on the upper cabinet that reveals the depth of the natural wood and so that the brightest spot in the kitchen will be the countertop where you use sharp knives in close proximity to your fingers and so that the shadows created by your body fall on the floor where light is less important.

THE RIGHT TIME

For decades, you could tell if a lighting designer was involved in a home by looking at the walls and noting that every light fixture was on its own dimmer. We were obsessed with dimmers. Switches were banned to garages and utility closets. I personally dimmed everything I could – the lights over the counter, the lights in my master closet, the lights above the sink, the lights in the hallway, the lights in the living room…you get the idea.

Humans need different amounts of light at different times of the day, so the simple binary of a switch is simply incapable of delivering what we need. In other words, we need light that changes. Light needs to be brighter in the morning and midday, then dimmer in the afternoon and dimmer still in the evening.

The recent scientific consensus on light and health, and the supporting color-tunable technologies, is driving this to a new level. In a few years you will be able to tell when a lighting designer was involved in a home by the lack of dimmers on the wall. Instead, there will be some kind of intelligent keypad that controls all the lights, responds to the human occupant, and aligns with natural light and biological rhythms.

So when we say “this is the light you should use in the evening,” we’re really saying “these lights are located below eye level to minimize intrusion into the high melanopic impact zones of your eye, and are dimmed to 30% to further reduce sleep disruption, and are 2200°K to reduce impact and help your body wind down for better sleep. And then the light will turn off and go completely dark so that you can sleep deeply. And then it will turn on at 5% if the sensor detects motion when you get up in the middle of the night, so your fully-dilated pupils will accept enough light for safety but not too much that your biological clock is reset.”

The next time I’m on an airplane and my seat mate asks about my profession, perhaps I should say “I help people get the right light in the right place at the right time.” After all, that’s what lighting designers do.

Check out a tongue-and-cheek video explaining lighting layout versus lighting design HERE.