This post might make some of my lighting colleagues a little angry, because I’m going to claim that light meters are nearly useless tools. I’m going to claim that the numbers we produce, the foot-candle levels or lux we calculate and measure, the math behind lighting design is all rather pointless.

(And before you write me angry note, please know that we use AGI32 to calculate light levels in critical locations, follow the IES recommended practices as best we can, and that my trusty Cooke cal-LIGHT 400 is within arms reach as I write this post. Math is important, but only sometimes, and less often than the younger version of myself wanted to think).

One of my first purchases as an independent lighting designer was a tool called a light meter. This calibrated, specialized, rather expensive tool does one thing: it converts the light at a given point into a number, either foot-candles or lux. I was very, very, very proud of my purchase. I carried my light meter like a Wild West sheriff carried a badge and a gun. I felt like the real deal.

I began every project with a carefully researched document listing out all the different recommended light levels that might apply to a project. I spent hours and hours setting up lighting calculations in specialized software, calculating and recalculating and recalculating until my numbers matched. Then I carried my trusty light meter into the field and checked my own math.

I can still remember the smug pride as I stood underneath the new streetlight our city put in our neighborhood for community feedback. None of my neighbors knew what magic I held in my hands, and I imagined the little crowd that night all thinking “this guy must be something special.” Fast forward 20 years and I might just call the younger me a lighting geek out of touch with reality.

The rest of the crowd that night was using better light meters than I was. They were using their eyes.

The more I understand of the human eye, mind, and body, the less I rely on mathematics as the primary tool of lighting design. The more I learn about lighting, the less I use my light meter.

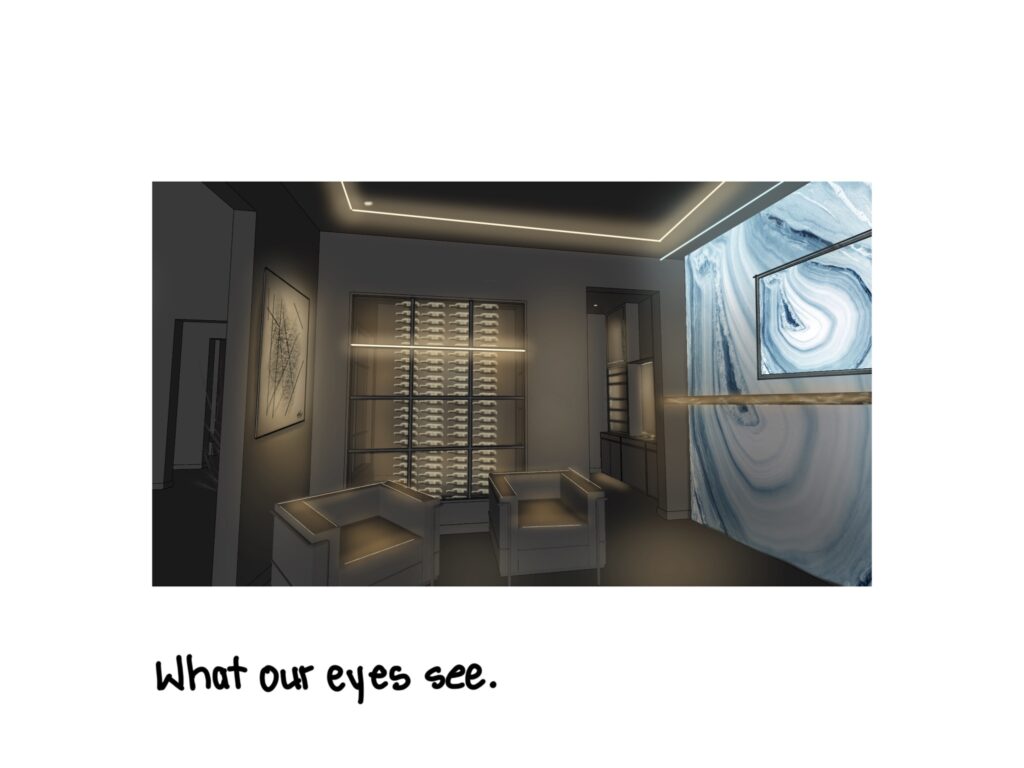

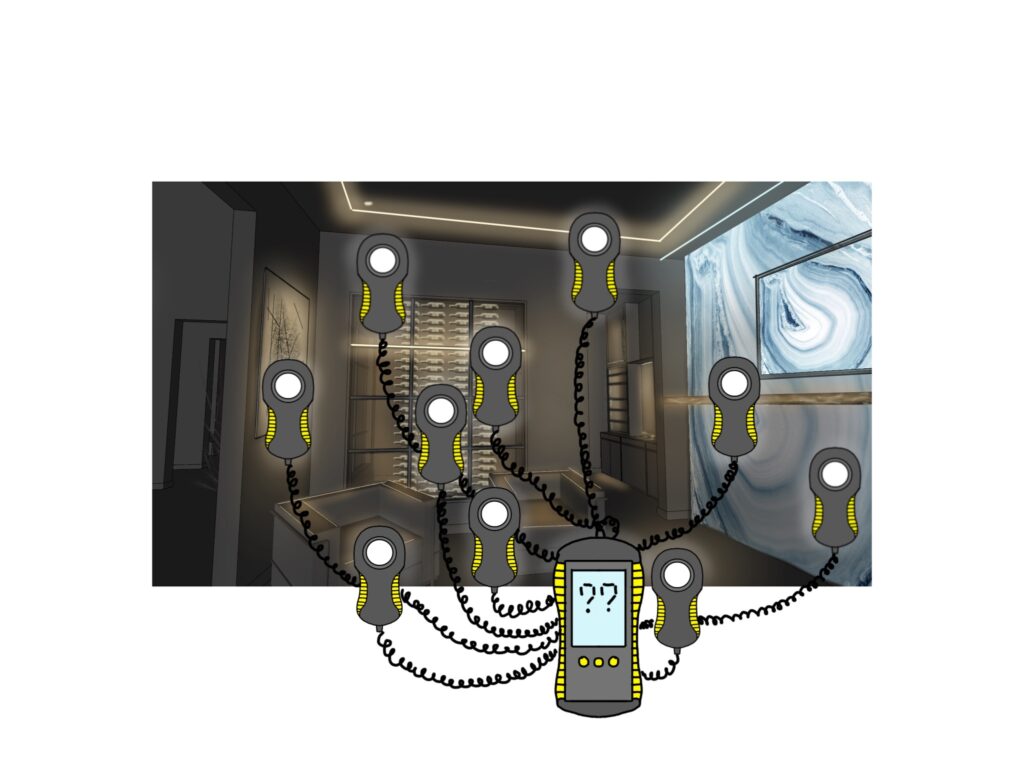

Our eyes see a picture, not a point. Our eyes take in thousands, perhaps millions, of light meter readings every second, every moment our eyes our open. In fact, one source claims that our eyes see in 576 megapixel resolution, or 576 million pixels. Each one of those “pixels” is a unique light meter reading.

Our light meters take one reading at one point.

Early in my career as an architectural lighting designer I was responsible for running computerized lighting calculations of a million square feet of open office space for a global banking corporation. I spent hours, even days, testing different fixtures and different layouts to maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of our designs. I tried different fixture spacings, different lamp combinations (this was back in the day when the T5 fluorescent was the next big thing), and different distances from the ceiling for our rows and rows of linear pendants.

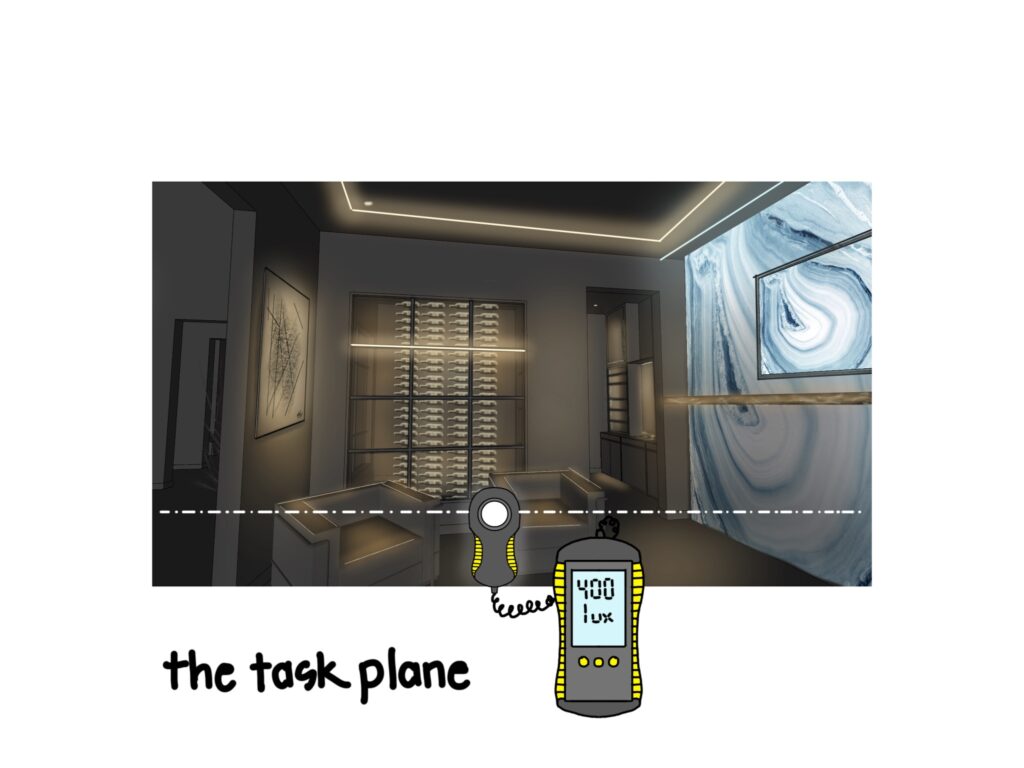

There were two critical calculations in each of these: light levels on the task plane (about 30″ above the floor, or common desk height) and uniformity ratios on the ceiling. The million square feet netted two numbers: 40 foot-candles on the task plane and a 3:1 ceiling uniformity ratio.

Two numbers.

In other words, of the 576 million possible readings that a single human might take in the room, I chose two of them upon which to base my design. And there would be 100 people or more in each section of the office space, so that would be 576 million possible readings times 100 people…and I have exceeded the capabilities of my brain to calculate the number of “light readings” taken every second of the work day.

A better way to predict the usability and comfort of the space would be to take more readings. 576 million more readings.

The illustration above demonstrates the absolute futility of accurately predicting what a human occupant will see, and does not even begin to address the more important question: how will the occupant feel?

If you’ve read this far you are either intrigued, bored, or angry. If the latter, please know that I advocate for the continued use of lighting calculations, just like I advocate for energy codes and electrical codes. We need to set a baseline. We need to set a bare minimum. But better lighting is not about meeting the minimums or covering your liabilities. Better lighting is about the 576 million light readings taken by your clients, and how they feel as a result.

I will tell Bob Dozier’s story until I die. Bob, an incredibly talented manufacturer’s rep, was on a visit to Peerless lighting in Berkeley when he met lighting guru Peter Ngai in Peter’s own lab. Bob took out his light meter and began to take readings. How much light does a genius like Peter need?

Peter simply gestured to a nearby open window. “Throw your light meter out the window,” he instructed. “You have two perfectly good light meters in your head.”