Yesterday I saw a LinkedIn post from another lighting designer featuring a photograph of a hallway under construction, with three parallel ceiling joists running down the hall. Each was filled with a round duct for heat and air conditioning.

There was no explanation; there need not be. One look and I understand the pain: there was absolutely no room above the ceiling for recessed lighting fixtures, the workhorse of hallway lighting. I bet there are a few boxes of very nice recessed lights sitting in a corner somewhere, planned for that space but now relegated to doorstops. Time to get creative!

And ductwork, while perhaps the most common source of conflict, is not the only one. Setting aside unexpected framing conflicts and joists too tightly spaced for lighting installation, there are a number of other reasons why lighting fixtures cannot always fit where intended.

This reality strikes me a bit like a high-stakes game of Tetris, with the blocks coming in faster and faster as we near drywall installation. Quick! Make space for something else!

I honestly do not know how builders cope with the constant jockeying for space above the ceiling. There are, of course, builders out there who carefully plan everything in advance, working out conflicts long before the ceiling is framed. Most builders do not have that luxury built into the timeline and budget, and in some cases it is more of a first-come, first-served method of conflict management. If the ducts were run first, then the electrician has to figure something out. And even the best builders can be surprised by an onsite change to ductwork or plumbing that renders planning obsolete.

Add in the need to run plumbing drains, water supplies, electrical wires, and audio-video infrastructure, and the “pick me!” voices are going to get noisy while the chances of conflict multiply exponentially. The more complex the project, the more likely someone is going to stake out a claim on valuable ceiling space that we also desperately want.

The result is that many projects are going to face a number of conflicts that require collaboration to prevent or correct.

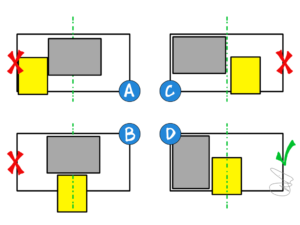

Let’s take a simple ceiling soffit, like above a kitchen counter. Running right down the middle of the soffit is a rectangular duct supplying air to a nearby room. Lighting fixtures are drawn on the plans also in the center of the soffit. Will it work?

- Leave the duct. We could leave the duct as placed and shove the light fixture to one side or another. This may be physically possible, but can dramatically alter the effectiveness of the light fixture. In this example, if the wall is on the left side, the fixture will now graze any artwork and cast harsh frame shadows instead of softly highlighting the art. If the wall is to the right side of the image, then the fixture may now be too far away to light the top of the cabinet or painting.

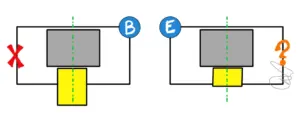

- In the second example we see an impractical solution – the light is pushed down below the ceiling. In addition to the rather obvious fact that recessed lights are not made to work like this (and would look terrible if they did), this could be a real problem for swinging cabinet doors.

- What if we shove the duct to one side? That will get our light fixture closer to where it needs to go, but it will still miss the centerline mark and have, to a lesser degree, all of the issues with example A.

- In this example, we can rotate the duct vertically, clearing enough space for the light fixture to live where it needs to live.

None of these is easy, only one of them puts the right light in the right place. Manufacturers have jumped in to help with super-shallow fixtures, some only 2” in depth.

These fixtures can be great problem solvers. 2” is not a lot of space, and sometimes that is the condition of the entire ceiling, like with concrete decks or Passiv Haus buildings with rigid insulation or SIPs.

Problem solved? If it were this easy, I would not be writing this blog post.

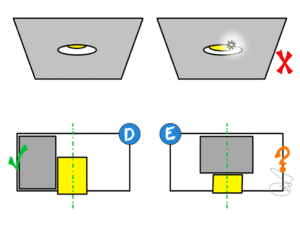

When solving the installation challenge with shallow housings, we may be creating a lifelong problem of increased glare for the homeowner. In other words, to save us a figurative headache during installation, we may be giving the occupants literal headaches for years to come.

Shallower light fixtures typically bring the light source closer to the ceiling plane, increasing the visibility of the bright emitter. This is generally not good for human eyes – we call it glare – and glare over time can cause eyestrain, headaches, and fatigue. It may not bother those of us involved with constructing the home – after all, we are probably never in the house at night.

That may not be true for the homeowners. Perhaps it is the very definition of “our job” to do a little extra work up front so the homeowner can live a better life?

I wish I had a magic fix for this one, but I do not. If anyone out there does, I would love to hear it!