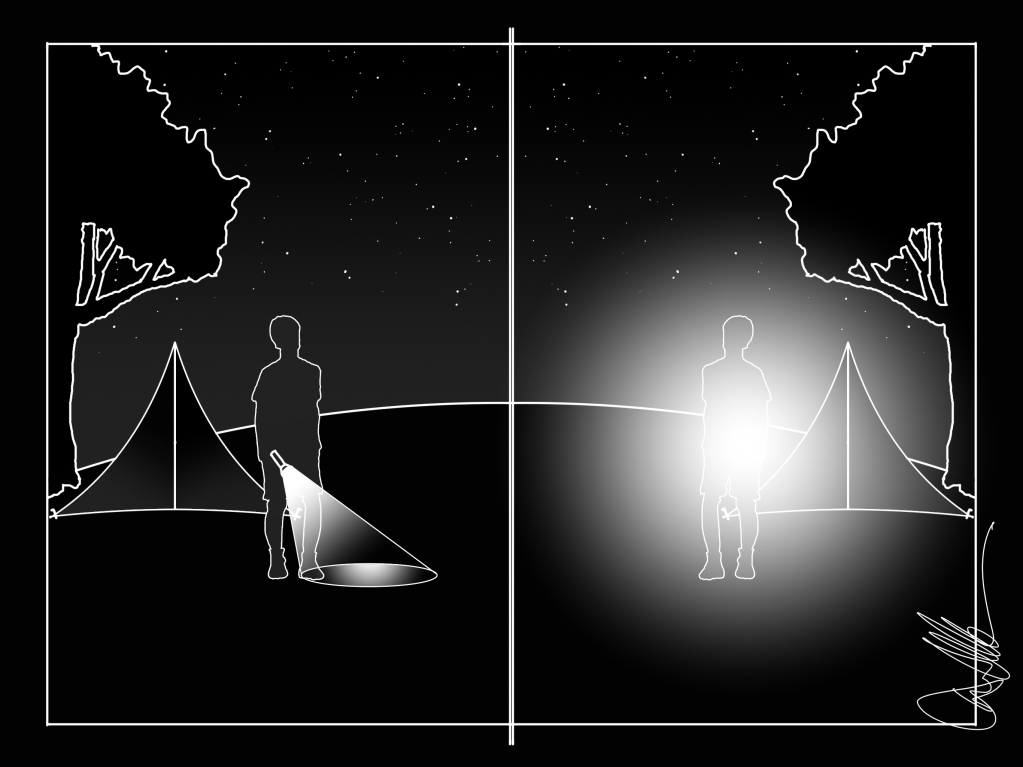

Over the last decade or so, our family has taken a number of camping trips to some of the darkest places in the United States. What was the first lesson we taught our children about nighttime in the campground? Never shine your flashlight in someone else’s face. What is the first thing that greets our guests, family, neighbors, and ourselves as we come home? Light shining right in our faces.

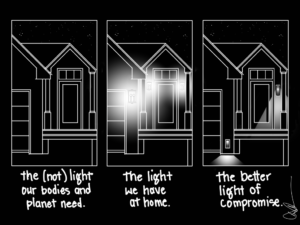

In my previous “Hello Darkness” post I shared a few reasons that darkness is vital to human wellbeing, good for the wallet, and critical to planetary health. The best light at night – from those perspectives – is absolutely no light at night, period. When the sun goes down, lights should turn off.

This is not a practical reality for most of us. Electrification has pushed us beyond our natural rhythms and the daily lives we now live require light at night. If we were careful about the light we consume after dark we might have minimized the negative effects, but instead we are ingesting way too much of a good thing. Way too much.

So what kind of light at night is acceptable? How can we minimize sleep disruption, increase our cognition, and regulate our body’s functions as they should be? Nearly every post on the blog is an attempt to answer these questions in one way or another, and this series will continue to explore the use of light at night in every space of the home. Today, however, I want to start outside, when we first come home.

If you live in a typical American house with a garage and a front porch, chances are good that you have light fixtures that shine most of their light out at your eyes instead of down at the ground. This makes it possible to see your front porch from a mile away but can make it harder to see the front steps when you are right there. The reason this light is so painful and counterproductive? Our iris.

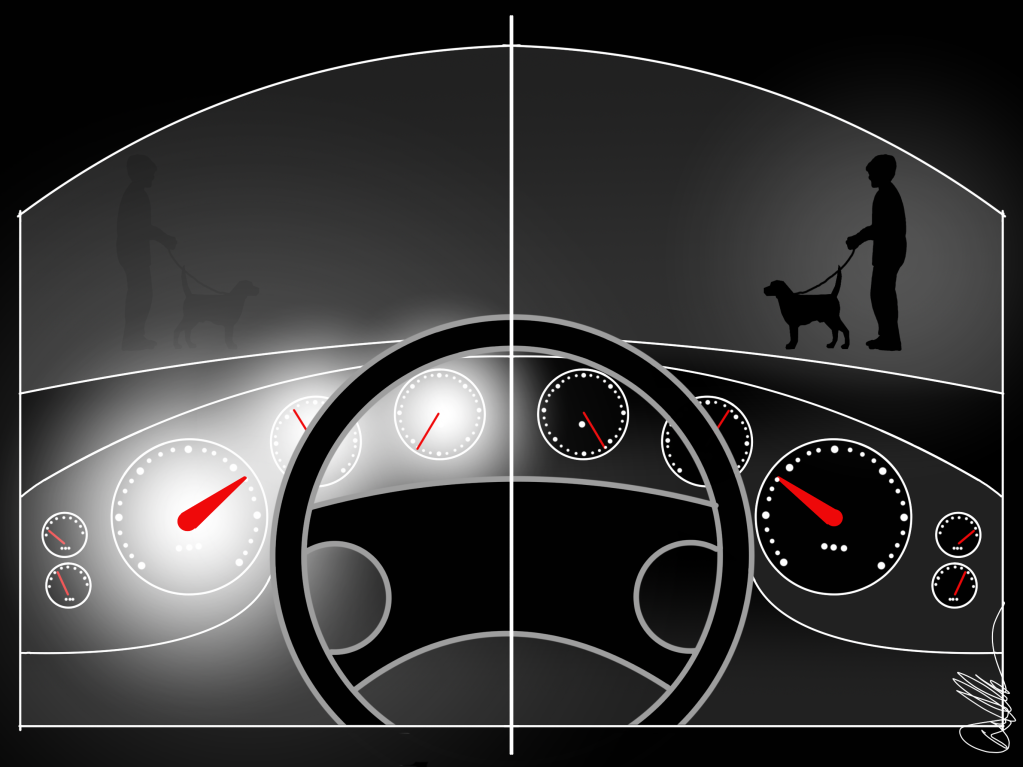

For decades, automobiles have had dimmers on the dashboard lights. My own vehicles have rotating nobs or wheels that gradually brighten or darken the speedometer, fuel gauge, radio controls, and more. If we do not make the effort to dim all of the lights in our home, why are they built into every automobile? Our iris.

The iris in our eye changes the size of the opening in our eyes that allow light through. The sensors on our retina- rods, cones, and others- can only take so much light before they overload. Staring into the sun can even blind us, permanently…we just cannot take too much of a good thing. So our irises open and close according to the light around us, constantly adjusting to ambient light conditions so that we can see clearly without pain. We can watch a movie indoors in deep darkness, then walk out to the parking lot on a summer afternoon and, after a minute or two of pain, be perfectly comfortable going for a sunny walk. The painful part is our iris adjusting too quickly to a rapid change in brightness. The iris does not work instantaneously, it’s like a muscle that needs time to adjust.

In automobiles, when we look at the dashboard, our irises will adjust to see the speedometer easily. When we look up at the street ahead, our irises will attempt to adjust to the darkness outside. Every time we change where we are looking, our irises attempt to keep up. If the dashboard is very bright, we will have difficulty when we look up at the night street. If the dashboard is too dark, we will strain to see the readouts.

So the automobile manufacturers include a dimmer that allows us to balance the two. If you haven’t done this before, while driving at night, adjust the dashboard dimmer so that the dashboard is a little bit darker than the street in front of you. This will make the street – and the obstacles, animals, pedestrians, and other players – easier to see.

Yes. Using less light will make it easier to see.

“But what about safety, David?”

The most common rebuttal to lighting that isn’t blinding is a concern over safety. We imagine that brighter light makes for safer places. So let’s go back to the automobile example.

You have your dashboard lights perfectly adjusted to balance with the outside lighting. Then a big truck with its bright high-beam headlights comes over the hill. Just like a bright porchlight, the bright light ahead of you makes it harder for you to see where you are going.

I have a new driver in my household, a teen who recently completed driver’s ed and received their license. Their instructor taught them to “look at the white line on the right of the road when oncoming headlights are blinding.” In other words, “we know that too much light will make it impossible for you to see the road well, so at least try to stay in your lane.”

The wrong kind of light makes it harder to see, not easier.

So what does this mean for our homes? First and foremost, we need less light at night than we think, and certainly far less light in our eyes than most of our porches provide. Approach your house like you are camping in a national forest in Wyoming. Do you want your house to shine a 100-watt flashlight in your face, or direct a 1-watt flashlight down onto the steps so you can avoid stumbling?

We do need light at night for our modern lifestyles and for safety when we are out and about at night. But we need less than you might think. Point it down. Dim it down. Being a good camper or driver is the same as being a good neighbor. Your wallet, your planet, and your eyes will thank you.

Read more about getting porch lights balanced HERE.

Read more about the iris and interior lighting HERE.

Read more of the Light Can Help Us series HERE.